Programme

Hector Berlioz

Harold in Italy, symphony with solo viola, Op. 16

Witold Lutosławski

Chain III (Czech premiere)

Ludwig van Beethoven

Symphony No. in 3 in E flat major, Op. 55 “Eroica”

Secure your seat for the 2025/2026 season – presales are open.

Choose SubscriptionHector Berlioz’s second symphonic work takes us to Italy. Accompanying us will be Lord Byron’s romantic hero Harold, whose voice will be Amihai Grosz, the principal violist of the Berlin Philharmonic. Upon returning from the musical universe of Witold Lutosławski, we will hear Beethoven’s majestic Eroica, originally dedicated by the composer to Napoleon.

Subscription series C

Hector Berlioz

Harold in Italy, symphony with solo viola, Op. 16

Witold Lutosławski

Chain III (Czech premiere)

Ludwig van Beethoven

Symphony No. in 3 in E flat major, Op. 55 “Eroica”

Amihai Grosz viola

Czech Philharmonic Youth Orchestra*

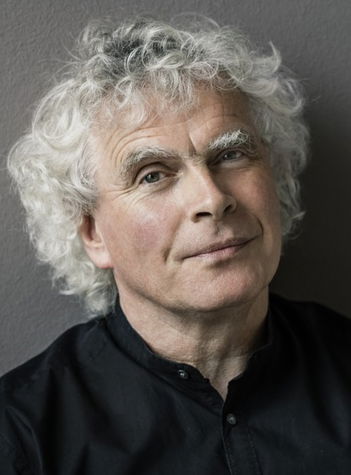

Simon Rattle conductor

Czech Philharmonic

* The Czech Philharmonic Youth Orchestra is playing Berlioz’s symphony Harold in Italy.

“Beethoven is dead, and Berlioz alone can revive him.”

– Nicolò Paganini, letter to Hector Berlioz dated 18 Dec. 1838

In 1830, Berlioz completed his Symphonie Fantastique, and he did not intend to write another symphonic work. He kept his word for three years until he got a commission from the virtuoso Nicolo Paganini. Shortly beforehand, the violinist had acquired a viola made by Antonio Stradivari, and he was looking for a composition to play on it.

When searching for a suitable subject, Berlioz considered a work with choir about the last moments of the life of Mary, Queen of Scots, but in the end an orchestral composition with viola solo won out. The work also reflected recollections of Berlioz’s earlier, rather unproductive stay in Italy as a winner of the Prix de Rome, a French stipend for gifted artists.

“It occurred to me to write a series of scenes for orchestra with solo viola involved as a more-or-less active character who always retains his own individuality. By placing it among poetic memories formed from my wanderings in the Abruzzi, I wanted to make the viola a kind of melancholy dreamer in the manner of Byron’s Childe-Harold. Thence the title: Harold in Italy.”

Paganini admired Berlioz, but the commissioned composition did not seem virtuosic enough for the presentation of a rare instrument, and he refused to play it. Four years later, however, when he attended the premiere in Paris at a concert conducted by Berlioz, he changed his opinion. He compared the composer to Beethoven and wrote him a bank draft for 20,000 francs, thanks to which Berlioz was able to compose a third symphony.

On the second half of the concert, we will hear Beethoven’s Third Symphony. “Beethoven, scornful and brutal, and yet gifted with deep sensitivity. It seems I would forgive him everything, his scorn and his brutality,” said Berlioz in deep admiration of his colleague’s work. The link between the two composers in the middle of the programme is Chain III by Witold Lutosławski.

Amihai Grosz viola

Simon Rattle conductor

We have seen one of today’s most distinguished conductors, Sir Simon Rattle, relatively often at the Rudolfinum in recent years. His long-term cooperation with the Czech Philharmonic has led to his appointment together with his wife, mezzo-soprano Magdalena Kožená, as Artist-in-Residence for the 2022/2023 season. At his appearances with the Czech Philharmonic, he has performed a number of symphonic works and, most notably, compositions for voices and orchestra from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the repertoire for which Rattle has been the most acclaimed. He appeared most recently at the Rudolfinum in February 2024 with the pianist Yuja Wang, with whom he made a Grammy-nominated recording from their joint tour of Asia in 2017. From the 2024/2025 season, he becomes the Principal Guest Conductor of the Czech Philharmonic.

A native of Liverpool and a graduate of the Royal Academy of Music has held a series of important positions in the course of his long career. He came to worldwide attention as the chief conductor of the Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, where he was employed for a full 18 years (for eight years as its music director); next came 16 years with the Berlin Philharmonic (2002–2018; artistic director and chief conductor) and six years with the London Symphony Orchestra. He opened the 2023/2024 season as chief conductor of the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra. He also leads the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment with the title of “principle artist”, and he is the founder of the Birmingham Contemporary Music Group. Besides holding full-time conducting posts, he maintains ties with the world’s leading orchestras and gives concerts frequently in Europe, the USA, and Asia.

He has made more than 70 recordings for EMI (now Warner Classics). He has won a number of prestigious international awards for his recordings including three Grammy Awards for Mahler’s Symphony No. 10, Brahms’s German Requiem, and Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms, which he recorded with the Berlin Philharmonic.

Besides the prizes mentioned above, Rattle’s long-term partnership with the Berlin Philharmonic also led to the new educational programme Zukunft@Bphil, which has achieved great success. Even after moving on from that orchestra, Rattle did not abandon his engagement with music education, and he has taken part together with the London Symphony Orchestra in the creation of the LSO East London Academy. Since 2019, that organisation has been seeking out talented young musicians, developing their potential free of charge regardless of their origins and financial situation.

Hector Berlioz

Harold in Italy, symphony with solo viola, Op. 16

Witold Lutosławski

Chain III

Ludwig van Beethoven

Symphony No. 3 in E Flat Major, Op. 55 (“Eroica”)

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN

(1770–1827)

The first composition that Ludwig van Beethoven intended to write for violin and orchestra dates from around 1792; this autonomous movement in C major is considered to be a fragment of an unfinished violin concerto. Around 1800 it was followed by Romance in G major, Op. 40, and Romance in F major, Op. 50. Some of Beethoven’s biographers consider these compositions to be parts of an unrealized plan for a concerto in a cyclic form, but there is no reliable evidence for this claim.

Concerto in D major for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 61 came into being within an extremely short period during November and December 1806. At the time, Beethoven was working on his Fifth Symphony, and both compositions have some elements in common. These include a series of timpani strokes at the beginning, the thematic treatment and the overall mood of both pieces. Violin Concerto was commissioned from Beethoven by Franz Clement (1780–1842), the concert master of the Orchestra of the Theater an der Wien. He premiered it there on 23 December 1806 on the occasion of his benefit concert, which also featured opera overtures by Étienne-Nicolas Méhul and Luigi Cherubini and Handel’s and Mozart’s vocal compositions. Clement’s name inspired Beethoven to a punning inscription “Concerto par Clemenza pour Clement” (Through Clemency for Clement). As a concert master, Clement participated in the presentation of a number of Beethoven’s works and also acted as a mediator between the often grumpy composer and impatient orchestral players (however, the first printed edition of the Violin Concerto was dedicated to Beethoven’s friend Stephan von Breuning). Clement allegedly got the finished score at the last minute, yet performed it brilliantly. As a violinist with excellent left-hand technique who still used an old-fashioned bow, he probably did not achieve the desired volume of sound. Beethoven later edited the solo part and returned to this piece once more in 1808, when he arranged it as a piano concerto at the request of the composer, pianist and publisher Muzio Clementi. On that occasion, he also revised the solo violin part, giving it the definitive form in which it is to be heard tonight.

The exposition of the first movement starts with the above-mentioned beat of the timpani. It is followed by five ideas that unfold from one another and are always accompanied by the rhythmic element of the timpani. The orchestra’s role goes beyond the usual accompaniment of a virtuoso concerto and leads to a symphonization which is the hallmark of violin concertos of the next generation. The first entry of the solo violin gives the impression of a cadenza, but here, too, the rhythmic pattern of the introduction, which goes through the whole development section, can be felt. In the recapitulation after the solo cadenza (which is entirely left to the soloist’s skills in improvising), the fourth of the ideas of the exposition returns as a small surprise for the listener, awaiting the usual conclusion. The second movement can also be considered a “romance”. The main idea is played by various instruments, and eventually it appears in the orchestral tutti; the second, less serious idea forms a contrasting relief. The cadenza leads into the final movement, Rondo, without a pause (attacca). The ritornello in the Rondo does not occur in a mechanical way, but is interrupted by two episodes. The composition ends with another extensive cadenza.

Franz Clement also appeared at the Theater an der Wien at the music academy where Beethoven’s Third Symphony was publicly performed for the first time. Its history has been analyzed in a great deal of literature, and the remarks of Beethoven’s biographers about this work go far beyond the music as such. The Third Symphony has been linked to Beethoven’s worldview and political beliefs, the reasons for its composition have been examined, and there is a number of hypotheses about its name and dedication. According to second-hand reports, the impulse for the symphony came from General Bernadotte, the French envoy to Vienna, whom Beethoven admired and whose salon he attended. The funeral march of the second movement, for example, was associated with the death of Admiral Nelson (however, at the time of his death at Trafalgar 1805, the symphony was already written); others linked it to Beethoven’s interest in ancient heroes and the like. The first sketches for the symphony come from 1802 when Napoleon Bonaparte became First Consul of the French Republic; Beethoven’s admiration for him and everything French went so far that he even intended to relocate to Paris. He wanted to dedicate his new symphony to Napoleon, but his patron, Prince Lobkowitz, did not like the idea. He offered Beethoven a considerable amount of money for this composition, reserving the right to perform it for six months. Beethoven resolved this issue by a compromise – he dedicated the symphony to Lobkowitz, while giving it the title “Bonaparte”. In mid-May 1804, however, Napoleon declared himself Emperor, and according to the testimony of Beethoven’s secretary, Ferdinand Ries, Beethoven tore the title page of the symphony in a fury. The original autograph score has not survived, but the changed name can be also seen in its copy, from which the original title was erased so forcefully that there is a hole in its place. The symphony was rehearsed in private in Lobkowitz Palace in Vienna in the late May and early June 1804 by an orchestra conducted by the concert master Anton Wranitzky. Lobkowitz took advantage of his right to the symphony, and let it be performed at his Jezeří Castle in northern Bohemia (in the presence of the Prussian Prince Louis Ferdinand, who was passing through the Czech lands on a diplomatic mission), and in January 1805 again in his palace in Vienna. The public premiere of the symphony took place on 7 April 1805 at the Theater an der Wien under Beethoven’s direction. The question remains who is referred to in the title Sinfonia Eroica, “composta per festeggiare il sovvenire di un grande Uomo” (Heroic Symphony, “composed to celebrate the memory of a great man”), under which the composition was published in the autumn of 1806. The “great man” seems to be Prince Louis Ferdinand of Prussia, who was killed on 10 October 1806 at the Battle of Saalfeld.

Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3 in E flat major “Eroica” was soon perceived as a revolutionary work both in terms of the social and artistic revolutions. For example, as early as 1839, it was written: “Beethoven transformed the storm of the world revolution into tones; with anxiety and yet full of enthusiasm, we listen how he dares to approach the limits of harmony.” The symphony represents a milestone in the development of Beethoven’s symphonic music as well as the genre as such. Above all, it is extremely extensive. The unusual number of three French horns in the instrumentation is sometimes related to Beethoven’s early problems with hearing, but it rather suggests a tendency to expand the orchestra’s sound capabilities, as they were fully developed in Romanticism through technical improvements in the design of instruments. The main theme does not consist only of a simple swinging between the notes of an E flat major chord that quickly stumbles on a dissonant C sharp, but the opening two tutti chords determine the rhythmic basis of the whole movement and give the background for all material. The development section, bringing in a new theme, which will also appears in the coda, is gaining in importance. The second movement is the first example of using the funeral march as a separate symphony movement, and scherzo is one of the most energetic in Beethoven’s oeuvre. The final movement features masterful variations, undeniably connected with Beethoven’s music for the ballet The Creatures of Prometheus, Op. 43, i.e., Fifteen Variations and Fugue, Op. 35 also called Eroica Variations. In many ways, Beethoven’s Eroica paved the way for the great symphonies of the next generation of composers.

Hector Berlioz’s second symphonic work takes us to Italy. Accompanying us will be Lord Byron’s romantic hero Harold, whose voice will be Amihai Grosz, the principal violist of the Berlin Philharmonic. Upon returning from the musical universe of Witold Lutosławski, we will hear Beethoven’s majestic Eroica, originally dedicated by the composer to Napoleon.