Programme

Kurt Weill

The Seven Deadly Sins, concert performance of the one-act opera (35')

— Intermission —

Antonín Dvořák

Slavonic Dances, Op. 46 (37')

Secure your seat for the 2025/2026 season – presales are open.

Choose SubscriptionFollowing his appointment as the Czech Philharmonic’s newest Principal Guest Conductor and Rafael Kubelík Chair, Simon Rattle announced his plans to devote himself to both music well-known and unknown by the orchestra. This is the reason for both the music of Dvořák and Weill on this programme. With the Slavonic Dances, Rattle returns to his childhood and the start of his life as a conductor; and with The Seven Deadly Sins, he brings to the Czech Philharmonic a piece he has already performed many times during his illustrious career with major orchestras worldwide.

Subscription series A

Kurt Weill

The Seven Deadly Sins, concert performance of the one-act opera (35')

— Intermission —

Antonín Dvořák

Slavonic Dances, Op. 46 (37')

Magdalena Kožená Anna / soprano

Aleš Briscein father / tenorAlessandro Fisher Andrés Moreno García brother / tenor

Lukáš Zeman brother / baritone

Florian Boesch mother / bass

Simon Rattle conductor

Czech Philharmonic

“The way my father and I played Dvořák's Slavonic Dances over and over again during my childhood and adolescence probably influenced to a large extent my becoming a musician. Coming here, to the birthplace of these dances, and recording them with the Czech Philharmonic is a really beautiful thing for me. And we'll see where it leads!” said Simon Rattle at the press conference at which he announced his plans with the leading Czech orchestra. A live recording of both series of Slavonic Dances will be made at concerts in the 2024/2025 season and should be released on the PENTATONE label in the autumn of 2025.

Programming Antonín Dvořák and Kurt Weill on a single evening exemplifies the artistic and dramaturgical ambitions that Rattle brings to the Czech Philharmonic. “I am fascinated by what pieces the orchestra plays often and what pieces remain rather rare. There are many areas we can explore. There are certainly pieces that I look forward to, because they are a kind of family heritage for the orchestra. But equally there are pieces that I would like to hear because they have not been played here before,” explained the current Chief Conductor of the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra.

And this is the case with The Seven Deadly Sins. With playwright Bertold Brecht, Kurt Weill wrote this “sung ballet” in Paris in the early 1930s just before they both emigrated from Nazi Germany. This was to be this creative powerhouse’s last collaboration in which Brecht employed his notorious acerbity and Weill took inspiration from the popular music of the day. This satirical one-act opera with its colourful cabaret-jazz score captures one of the celebrated musical styles of the first half of the twentieth century. And as far as the deadly sins are concerned, to understand the drama, one only needs to remember the worst sin of all: to not have two pennies to rub together.

After the concert on 10 April we invite you to an aftertalk with Simon Rattle in the Dvořák Hall. David Mareček, General Director of the Czech Philharmonic, will moderate.

You can watch the concert and the aftertalk live on our YouTube channel.

Magdalena Kožená soprano

Like on many past occasions, Magdalena Kožená is returning to her homeland with her husband, Sir Simon Rattle. Kožená, a graduate of the Brno Conservatoire and of the Academy of Performing Arts in Bratislava, came to worldwide attention thanks in part to victory at the International Mozart Competition in 1995; four years later she signed an exclusive contract with the label Deutsche Grammophon, for which she has released many award-winning recordings (Gramophone Award, Echo Klassik, Diapason d’Or etc.). She divides her performing activities between recitals, concert appearances, and operatic roles including regular guest appearances at New York’s Metropolitan Opera. She also performs in such non-classical genres as swing and flamenco. Her classical repertoire is of remarkable breadth, ranging from the baroque era and collaborations with ensembles specialising in early music to the classical and romantic repertoire, in which she has won fame in part as a proponent of Czech music, and onwards to the music of today.

Aleš Briscein tenor

Two-time Thalia Award winner Aleš Briscein is a sought-after guest at Czech and foreign theatres and concert halls. He originally studied clarinet and saxophone, then opera singing at the Prague Conservatoire. Thereafter, he furthered his studies at the University of West Bohemia in Pilsen. He has performed at the prestigious Salzburg, Edinburgh, and Prague Spring festivals, including having sung the main tenor role of part Jonathan in the world premiere of the oratorio Judas Maccabeus by Sylvie Bodorová. For the Decca label, he make a CD recording of Pavel Haas’s opera The Charlatan, and he has sung in Alban Berg’s Wozzeck in Valencia and in Zemlinsky’s opera Der Zwerg with the Odyssey Opera in Boston. His range of repertoire is very broad, and he enjoys devoting himself to early music and sacred works. Although he has appeared in concert collaborating with many important orchestras, his career focuses on opera. He is a regular guest in Prague with the National Theatre and the State Opera, and abroad he works in close cooperation with the Opéra National de Paris. He has also appeared on the stages of the Teatro Real in Madrid, Vienna’s Volksoper, Berlin’s Komische Oper, the Bavarian State Opera, and Oper Graz.

Andrés Moreno García tenor

Lukáš Zeman baritone

Although the Czech baritone Lukáš Zeman appears in operas from time to time in this country (at the theatres in Ostrava and Pilsen) and on Czech concert stages (Collegium 1704), he has become especially famous abroad, where his studies took him: after studying singing and bassoon at the Jan Neruda Grammar School, he studied singing at the Mozarteum in Salzburg, the Royal Conservatoire of The Hague, the Luigi Cherubini Conservatoire in Florence, and the Dutch National Opera Academy in Amsterdam. On such famed opera stages as the Komische Oper in Berlin, the Teatro alla Scala in Milan, Florence’s Teatro Maggio, and the Opéra National de Lyon, he has sung a number of roles from his vast repertoire ranging from Monteverdi to works of the 20th and 21st centuries, including the opera Die Soldaten by Bernd Alois Zimmermann, which he performed with the ensemble Il canto di Orfeo at La Scala. Besides appearing in Europe, he has also visited concert stages in India, Israel, the USA, and China. His discography includes recordings of some forgotten works, reflecting not only operatic, concert, and chamber literature, but also Zeman’s interest in the art song. In 2020 he received the Thalia Award in the field of opera for his outstanding performance as Count Almaviva in The Marriage of Figaro.

Florian Boesch bass

The Austrian baritone Florian Boesch is a versatile singer in terms of genre and range of repertoire. This is perhaps best seen in his operatic roles, where he feels equally at home in Purcell or Weill, Mozart or Berg. Notwithstanding his many solo performances with distinguished orchestras and conductors, in the concert hall he has come to listeners’ attention mainly thanks to his close professional relationship with Nikolas Harnoncourt. He made his debut with the Czech Philharmonic in the 2023/24 season as a soloist in Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. His recordings reflect great interest in romantic song cycles, for the interpretation of which he has received such honours as the BBC Music Magazine Award. He is heard in song recitals at the festivals in Salzburg and Edinburgh, at Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw, at New York’s Carnegie Hall, and at London’s Wigmore Hall, where he has also served as an artist-in-residence. Boesch received his vocal training first from his grandmother Ruthilde Boesch and then from Robert Holl at the Musikhochschule in Vienna. He now teaches at Vienna’s Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst.

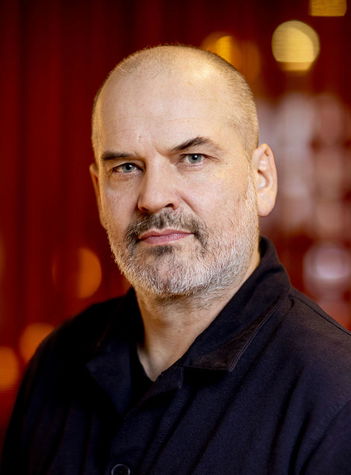

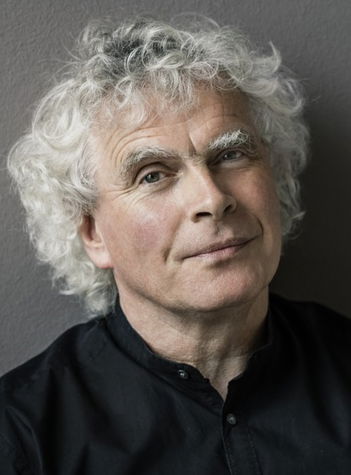

Simon Rattle conductor

We have seen one of today’s most distinguished conductors, Sir Simon Rattle, relatively often at the Rudolfinum in recent years. His long-term cooperation with the Czech Philharmonic has led to his appointment together with his wife, mezzo-soprano Magdalena Kožená, as Artist-in-Residence for the 2022/2023 season. At his appearances with the Czech Philharmonic, he has performed a number of symphonic works and, most notably, compositions for voices and orchestra from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the repertoire for which Rattle has been the most acclaimed. He appeared most recently at the Rudolfinum in February 2024 with the pianist Yuja Wang, with whom he made a Grammy-nominated recording from their joint tour of Asia in 2017. From the 2024/2025 season, he becomes the Principal Guest Conductor of the Czech Philharmonic.

A native of Liverpool and a graduate of the Royal Academy of Music has held a series of important positions in the course of his long career. He came to worldwide attention as the chief conductor of the Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, where he was employed for a full 18 years (for eight years as its music director); next came 16 years with the Berlin Philharmonic (2002–2018; artistic director and chief conductor) and six years with the London Symphony Orchestra. He opened the 2023/2024 season as chief conductor of the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra. He also leads the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment with the title of “principle artist”, and he is the founder of the Birmingham Contemporary Music Group. Besides holding full-time conducting posts, he maintains ties with the world’s leading orchestras and gives concerts frequently in Europe, the USA, and Asia.

He has made more than 70 recordings for EMI (now Warner Classics). He has won a number of prestigious international awards for his recordings including three Grammy Awards for Mahler’s Symphony No. 10, Brahms’s German Requiem, and Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms, which he recorded with the Berlin Philharmonic.

Besides the prizes mentioned above, Rattle’s long-term partnership with the Berlin Philharmonic also led to the new educational programme Zukunft@Bphil, which has achieved great success. Even after moving on from that orchestra, Rattle did not abandon his engagement with music education, and he has taken part together with the London Symphony Orchestra in the creation of the LSO East London Academy. Since 2019, that organisation has been seeking out talented young musicians, developing their potential free of charge regardless of their origins and financial situation.

Kurt Weill

The Seven Deadly Sins, concert performance of the one-act opera

In 1933, the choreographer Georges Balanchine established the dance group “Les Ballets 1933” in Paris. A wealthy Englishman named Edward James became their patron, promising to fund the ensemble if a role could be found for his wife, the dancer and actress Tilly Losch and if Kurt Weill composed the music for it. The composer, who had fled Germany after the Nazis seized power and was looking for work in Paris, gladly accepted the offer. However, he also made a condition of his own. He was determined not to write pure ballet music, but instead to create a “ballet chanté” – a ballet with singing. Jean Cocteau was considered as the author of the text, but he turned down the offer, so Edward James suggested Bertold Brecht. Brecht had left Berlin the day after the Reichstag fire and fled to Switzerland, but upon receiving the invitation from Paris, he immediately departed for the French capital despite the fact that he and Weill had not seen eye-to-eye during rehearsals of the opera Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny (The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny, premiered in 1930 in Leipzig). The sung ballet Die sieben Todsünden (The Seven Deadly Sins) became their last collaborative work.

The action tells the story of a girl named Anna, who is sent by her family to American cities to earn money as a dancer so her family can buy a little house in Louisiana. Anna passes through seven cities, and in each she is confronted by one of the deadly sins. Anna is torn between the dictates of morality and the capitalist world, which follows different rules. Anna’s split personality is presented on stage by two characters, a singer (Anna I) and a dancer (Anna II) who comments on the words of Anna I only briefly. The singing Anna I thinks pragmatically, while Anna II, who expresses herself through movement, has difficulty submitting, but Anna I has power over her. Brecht’s wife Lotte Lenya (1898–1981) sang the role of Anna I. In accordance with patron’s condition, the dancer was the Vienna native Tilly Losch (1903–1975). The stage design was by Caspar Neher (1897–1962), and the performance was led by Maurice Abravanel (1903–1993), a conductor of Greek descent who was Weill’s pupil and collaborator for many years.

The music consists of seven movements corresponding to the seven deadly sins that have been part of Catholic tradition since the sixth century, during the era of Pope Gregory I (Saint Gregory the Great). The work is framed by a Prologue and an Epilogue. In an interview in 1930, Weill announced that he no longer intended to write the songs that had been the basis for his pervious collaborations with Brecht in Die Dreigroschenoper (The Threepenny Opera) or the school-opera Der Jasager (The Yes Sayer), and that from then on he wanted to write in “self-contained musical forms”. The Seven Deadly Sins amounts, in a certain sense, to a dance suite with the choice of a particular dance for each movement (each sin): the waltz, foxtrot, shimmy, tarantella... The family of four members consists of a quartet of male voices, evoking the 19th-century tradition of men’s vocal ensembles, but also bringing to mind the similar ensembles of Weill’s day, such as the Comedian Harmonists, who were enormously popular between 1928 and 1934. Weill employs ironic exaggeration; having the role of the mother sung by a bass makes a particularly grotesque impression. All of the movements are tied together by the striking motif of Anna’s sorrow. The instrumentation calls for a full wind section, percussion, harp, piano, banjo, and guitar, and the strings are given an important role for the first time in Weill’s music.

The premiere was given with the French title Les Sept Péchés Capiaux together with several shorter ballets on 7 June 1933 at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées. The singing was in German, and the work’s reception was reportedly mixed. According to a different report, however, the response to the ballet led to the adding of another five performances to the two showings that had originally been planned. At the end of June, the ensemble departed for London, where the ballet was performed at the Savoy Theatre in English with the title Anna-Anna. There was only one more production during Weill’s lifetime, in 1936 in Copenhagen. In early 1935, Kurt Weill and Lotte Lenya left Europe. In the USA, the last chapter of Weill’s career began on Broadway. He died in New York on 3 April 1950.

Antonín Dvořák

Slavonic Dances, Op. 46

Since ancient times, dance rhythms have been finding their way into instrumental music in forms that go beyond the role of an accompaniment to dancing. Baroque suites employed the rhythms of Italian and French dances, in music by Bach and Telemann we find the designation alla polacca, while Haydn and others used alla ungarese, and the menuet became an obligatory movement in symphonic form. In the 19th century, the waltz, polka, and mazurka reigned supreme, and not only on the dance floor. Antonín Dvořák used the furiant, a Czech dance, for the scherzo of his Sixth Symphony, and Bedřich Smetana wrote a polka as a movement of his First String Quartet.

Antonín Dvořák wrote his series of Slavonic Dances at the suggestion of the Berlin publisher Fritz Simrock. In 1878, Simrock had published Dvořák’s Moravian Duets at the recommendation of Johannes Brahms, and their success led the publisher to commission a new work, this time a cycle of dances. Simrock had a rather clear idea of what he wanted, suggesting the arranging of Czech and Moravian dances for piano four-hands “in the manner of Brahms’s Hungarian dances”, in which the original melodies could be combined with Dvořák’s own musical ideas. On 24 March 1878, Dvořák wrote to Brahms, informing him about Simrock’s commission and asking for permission to use Brahms’s Hungarian Dances as his model. That same year (1878), he wrote his first series of eight Slavonic Dances, Op. 46, originally intended (like Brahms’s cycle) for piano four-hands. The series was a huge success, and the Berlin publisher commissioned a continuation in 1885. That time, however, Dvořák was initially hesitant: “It’s damned hard to do the same thing twice”, he complained to Simrock. In the end, however, he found inspiration for a second series also containing eight dances, and like in the first instance, he created an orchestral version at the same time as a version for piano four-hands. The second series goes beyond Czech dances to include the broader Slavic region, with appearances by the Moravian-Silesian odzemek, the Ukrainian dumka, the Polish polonaise, and the Serbian kolo. Dvořák (unlike Brahms) does not quote folk melodies directly in any of the dances, which are masterful stylisations of characteristic elements; these unique compositions are pure Dvořák. Although the types of dances are identifiable on the basis of their rhythms, Dvořák did not assign them titles, but only tempo markings. In the first series of Slavonic Dances, we recognise the polka, the skočná polka, the sousedská, and the furiant. The Slavonic Dances have taken their rightful place among Dvořák’s most popular works, and they spread all around the world in their orchestral from soon after they had been written.

Following his appointment as the Czech Philharmonic’s newest Principal Guest Conductor and Rafael Kubelík Chair, Simon Rattle announced his plans to devote himself to both music well-known and unknown by the orchestra. This is the reason for both the music of Dvořák and Weill on this programme. With the Slavonic Dances, Rattle returns to his childhood and the start of his life as a conductor; and with The Seven Deadly Sins, he brings to the Czech Philharmonic a piece he has already performed many times during his illustrious career with major orchestras worldwide.