1 / 6

Czech Philharmonic • Yokohama

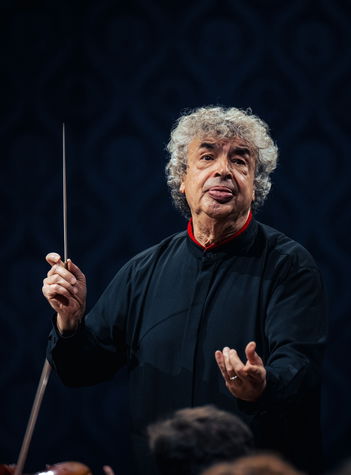

After a four–year absence, the Czech Philharmonic is also playing in Yokohama, and with this concert it ends its autumn tour of Asia. The final concert is on a grand scale with Antonín Dvořák’s last two symphonies, the Eighth (“English”) and Ninth (“From the New World”) under the baton of the orchestra’s chief conductor Semyon Bychkov.

Programme

Antonín Dvořák

Symphony No. 8 in G major, Op. 88

Antonín Dvořák

Symphony No. 9 in E minor, Op. 95 “From the New World”

Performers

Semyon Bychkov conductor

Czech Philharmonic

To purchase online, visit the event presenter's website.

Performers

Semyon Bychkov conductor

In addition to conducting at Prague’s Rudolfinum, Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic in the 2023/2024 season, took the all Dvořák programmes to Korea and across Japan with three concerts at Tokyo’s famed Suntory Hall. In spring, an extensive European tour took the programmes to Spain, Austria, Germany, Belgium, and France and, at the end of year 2024, the Year of Czech Music culminated with three concerts at Carnegie Hall in New York.

Among the significant joint achievements of Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic is the release of a 7-CD box set devoted to Tchaikovsky’s symphonic repertoire and a series of international residencies. In 2024, Semjon Byčkov with the Czech Philharmonic concentrated on recording Czech music – a CD was released with Bedřich Smetanaʼs My Homeland and Antonín Dvořákʼs last three symphonies and ouvertures.

Bychkovʼs repertoire spans four centuries. His highly anticipated performances are a unique combination of innate musicality and rigorous Russian pedagogy. In addition to guest engagements with the world’s major orchestras and opera houses, Bychkov holds honorary titles with the BBC Symphony Orchestra – with whom he appears annually at the BBC Proms – and the Royal Academy of Music, who awarded him an Honorary Doctorate in July 2022. Bychkov was named “Conductor of the Year” by the International Opera Awards in 2015 and, by Musical America in 2022.

Bychkov began recording in 1986 and released discs with the Berlin Philharmonic, Bavarian Radio, Royal Concertgebouw, Philharmonia Orchestra and London Philharmonic for Philips. Subsequently a series of benchmark recordings with WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne featured Brahms, Mahler, Rachmaninov, Shostakovich, Strauss, Verdi, Glanert and Höller. Bychkov’s 1993 recording of Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin with the Orchestre de Paris continues to win awards, most recently the Gramophone Collection 2021; Wagner’s Lohengrin was BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Year (2010); and Schmidt’s Symphony No. 2 with the Vienna Philharmonic was BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Month (2018).

Semyon Bychkov has one foot firmly in the culture of the East and the other in the West. Born in St Petersburg in 1952, he studied at the Leningrad Conservatory with the legendary Ilya Musin. Denied his prize of conducting the Leningrad Philharmonic, Bychkov emigrated to the United States in 1975 and, has lived in Europe since the mid-1980’s. In 1989, the same year he was named Music Director of the Orchestre de Paris, Bychkov returned to the former Soviet Union as the St Petersburg Philharmonic’s Principal Guest Conductor. He was appointed Chief Conductor of the WDR Symphony Orchestra (1997) and Chief Conductor of Dresden Semperoper (1998).

Compositions

Antonín Dvořák

Symfonie č. 8 G dur op. 88 „Anglická“

Rok 1889, ve kterém vznikla Symfonie č. 8 G dur op. 88, byl pro jejího autora úspěšný. Dostal nabídku profesora skladby na Pražské konzervatoři, Národní divadlo mu uvedlo premiéru opery Jakobín, byl vyznamenán Řádem železné koruny. Dvořák se nacházel v pozitivním životním období, ve kterém u něj sílil pocit vyrovnanosti a životní radosti.

Zájem o skladatelovy kompoziční aktivity byl dále posílen jeho úspěšnými pobyty v Anglii. Svému anglickému příteli klavíristovi a skladateli Francescu Bergerovi v dopise ze dne 8. září 1889 píše: „Velmi děkuji za Váš laskavý dopis, ve kterém se mě ptáte, zda mám něco nového pro Vaše koncerty. Pravděpodobně to bude nová symfonie, na které nyní pracuji; je zde pouze otázka, zda budu schopen ji dokončit včas.“Do práce na Osmé symfonii byl Dvořák ponořen od 28. srpna do 8. listopadu, a to převážně na svém letním sídle ve Vysoké, kde se cítil nejlépe.

Dobrá tvůrčí atmosféra byla ale narušena roztržkou s jeho „dvorním“ nakladatelem Simrockem. Vydavateli se Dvořákovy finanční požadavky zdály přehnané. Snažil se ho přimět ke komponování drobnějších a jednodušších skladeb, neboť velká a náročná orchestrální díla se mu nezdála dostatečně rentabilní. Autor ovšem nehodlal slevit ze svých uměleckých představ, a tak na tři roky přerušil se Simrockem spolupráci. Svůj opus 88 vydal u londýnské firmy Novello. Symfonie tak proto získala později podtitul „Anglická“.

Osmá symfonie si v základních rysech – čtyřvětosti a tempovém rozvržení vět – zachovává stavbu klasické symfonie. Dílo ale překvapuje mnoha inovacemi, pestrým sledem proměnlivých nálad od pastorálních obrazů přes intonace taneční a pochodové až k dramaticky vypjatým plochám. Je to kantabilní a diatonická skladba, ze které je patrná skladatelova náklonnost k české a slovanské lidové hudbě. Jak sám autor poznamenává, usiloval o zpracování témat a motivů v jiných než „obvyklých, všeobecně užívaných a uznaných formách".

Premiéra se uskutečnila pod Dvořákovým vedením 2. února 1890 v Rudolfinu v rámci populárních koncertů Umělecké besedy a následně 24. dubna téhož roku v Londýně při koncertu tamní Filharmonické společnosti v St. James’s Hall. Dvořák symfonii následně dirigoval ještě mnohokrát: 7. listopadu 1890 ve Frankfurtu nad Mohanem, 15. června 1891 v Cambridge při příležitosti udělení čestného doktorátu tamní univerzitou, 12. srpna 1893 v Chicagu a 19. března 1893 znovu v Londýně. Ohlasy, které následovaly po provedeních, jsou samostatnou kapitolou. Dvořák byl anglickým tiskem označen za jediného z žijících skladatelů, který může být oprávněně nazýván Beethovenovým nástupcem: „Ten jediný, ačkoli se stejně jako Brahms snaží držet Beethovenovy školy, je schopen přinést do symfonie zřetelně nový prvek.“

Vídeňský kritik Eduard Hanslick zase píše: „Celé toto Dvořákovo dílo, jež patří k jeho nejlepším, lze chválit za to, že není pedantické, ale při vší uvolněnosti nemá zároveň k ničemu tak daleko jako k naturalismu. Dvořák je vážným umělcem, který se mnohému naučil, ale navzdory svým vědomostem nepozbyl spontánnost a svěžest. Z jeho děl mluví originální osobnost a z jeho osobnosti vane osvěžující dech něčeho neopotřebovaného a původního.“

Zanedbatelný není ani komentář samotného skladatele po Londýnské premiéře: „Koncert dopadl skvěle, ba tak, jak snad nikdy předtím dříve. Po první větě byl aplaus všeobecný, po druhé větší, po třetí velmi silný tak, že jsem se musel několikrát obracet a děkovat, ale po finále byla pravá bouře potlesku, obecenstvo v sále, na galeriích, orkestr sám, i za ním u varhan sedící, tleskalo tolik, že to bylo až hrůza, byl jsem několikrát volán a ukazovat se na pódium – zkrátka bylo to tak hezké a upřimné, jak to bývá při premiérách u nás doma v Praze. Jsem tedy spokojen a zaplať pánbůh za to, že to tak dobře dopadlo!“

Antonín Dvořák

Symphony No. 9 in E minor, Op. 95, “From the New World”

Dvořák’s prestigious invitation to New York did not come out of nowhere. For years, his music had already been familiar in the United States, and American newspapers had been writing about his successes in Europe as a composer and conductor. Above all, however, for America Dvořák was iconic as a national composer. “Americans expect great things from me, and above all, supposedly, that I will show them the way to the promised land and to the realm of new, independent art, in short, how to create the music of a nation!! […] Certainly, this is an equally great and beautiful task for me, and I hope I shall have the good fortune to succeed with God’s help. There is more than enough material here,” wrote the composer to his friend Josef Hlávek after arriving in America. Dvořák did, in fact, delve into America’s musical material with great interest, as is revealed in an interview for the New York Herald: “Since I have been in this country I have been deeply interested in the national music of the negroes and the Indians. […] I intend to do all in my power to call attention to this splendid treasure of melody which you have.” Dvořák did not borrow the melodies, however. He created his own melodies using many of the characteristic features of folk songs that he combined with the essence of American folklore. In addition, the motifs from the new Symphony in E minor, Op. 95, “From the New World”, did not come into the world instantly in the form in which we now know them. This is documented by the composer’s sketches, in which the now famous themes appear still with many deviations from the final version. It is clear that during the compositional process, Dvořák was giving ever deeper expression to the “American spirit” that he wanted the music to embody, adding syncopations including a special rhythm known as the “Scotch snap”, highlighting the pentatonic scale etc. However, his new symphony was by no means an attempt to do everything differently from his previous symphonies. As he was finishing the score, he brought this up in a letter to his friend Göbl: “I’m just now finishing my Symphony in E minor, which will be strikingly different from my earlier ones, mostly in terms of melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic figures—just my orchestration has not changed, something in which I probably will not advance any further, nor do I wish to, and I have my reasons.”

The composer also mentioned the work’s tempestuous reception at the premiere at New York’s Carnegie Hall in December 1893 (Anton Seidl conducted the New York Philharmonic) in a letter to his publisher Fritz Simrock in Berlin: “The symphony’s success on December 15th and 16th was magnificent; the newspapers say that no composer has ever before achieved such a triumph. I was seated in a box, the hall was occupied by New York’s most elite public, and the people applauded so much that I had to wave from my box like a king to show my gratitude! Like Mascagni in Vienna (don’t laugh!). You know that I prefer to try to avoid such ovations, but I had to do this and show myself.” The composer did not inscribe the title “From the New World” on the score’s title page until a few months after finishing the work; it was on the very day that he handed the score over to the conductor for rehearsals. The title of the first work he had written in America gave rise to a great deal of comment in newspaper articles. Having read them, the composer supposedly remarked with a smile: “Well, it seems I have confused their minds a bit.”