During his lifetime Nikolai Kapustin’s music was always underappreciated. A lover of classical jazz and a pianist, composer and arranger by profession, Kapustin in his compositions combined jazz elements with classical musical forms. “I was never a jazz musician,” he said. “I am not interested in improvisation – and what is a jazz musician without improvisation? All my improvisations are written, of course.” Interest in Kapustin’s work has grown sharply thanks to a handful of performers – the pianists Steven Osborne, Marc-André Hamelin, Daniel del Pino and Masahiro Kawakami – who have presented his sonatas, preludes and fugues on international stages. At home in Soviet Russia he was only tolerated and the ice melted slowly. After the composer’s death in 2020, as is usually the case, interest in Kapustin’s work skyrocketed. The New York Times has published an extensive retrospective of his life and work, Kapustin’s original recordings are appearing and new ones are being made. Recently, a CD recording of Kapustin’s concertos and orchestral works performed by the Württemberg Chamber Orchestra conducted by Case Scaglione has attracted attention.

Nikolai Girshevich Kapustin was born in Gorlovka in the former USSR (now Horlivka in the war-torn Donbas region of eastern Ukraine). When he was four years old, his family, fleeing from the Nazis, was evacuated to Kyrgyzstan. At the age of seven Kapustin began playing the piano and at 14, after moving to Moscow, he was accepted at the Academic Music College into the class of Avrelian Rubbakh. This free-spirited teacher encouraged Kapustin’s interest in jazz. Kapustin devoured recordings of Glenn Miller, Benny Goodman and Louis Armstrong at night on the radio station Voice of America and soon began a career of a jazz pianist at the National Hotel in Moscow. At the same time he continued his university studies at the Moscow Conservatory in the class of Alexander Goldenweiser.

After his graduation in 1961, Kapustin became the jazz pianist in Oleg Lundström’s Big Band. At the same time, he began composing and arranging for this ensemble, which was the showcase of Soviet jazz during the Khrushchev and Brezhnev eras. After marrying and starting a family, Kapustin chose a less time-consuming job with the Blue Screen radio orchestra and the State Cinematography Symphony Orchestra. From 1980 onwards, he stopped giving public solo concerts and only recorded. His last album was released in 2004.

Although Kapustin did not officially study composition, he wrote a total of 161 mostly piano opuses, including 20 sonatas, 6 concertos, as well as variations, etudes, and chamber piano trios. From the perspective of the modern listener, his music sounds modest, lucid and sometimes almost archaic, as if it were intended for the dance halls of the 1930s. It combines jazz with classical music forms. For example, Suite in the Old Style integrates the character of jazz improvisation into the structure of the dances of a Baroque suite in the style of Johann Sebastian Bach. The same can be said of the monumental 24 Preludes and Fugues for Piano, Op. 82, inspired by both Bach and Shostakovich, or Piano Sonatina, Op. 100, which is a “jazz piece of the Haydn type”.

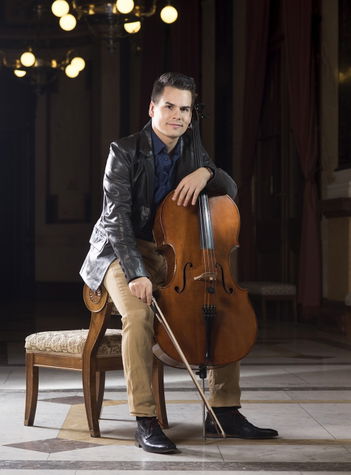

The three works by Nikolai Kapustin to be heard today were dedicated to his friend, cellist Alexander Zagorinsky (born 1962), who premiered two of his cello concertos and two sonatas. In 1999, Kapustin composed three short pieces for cello and piano, Elegy, Burlesque and Nearly Waltz. Nearly Waltz, Op. 98, has the tempo and feel of a waltz, but because of the irregular alternation of the time signature between 5/4 and 3/4 it is not possible to dance to it. Elegy, Op. 96, might aspire to be a classical music meditation if it were not for the explosively improvisational middle section. Burlesque, Op. 97, employs jazz elements even more prominently, especially thanks to the assertively playing piano.