1 / 6

Czech Philharmonic • Steven Osborne

The Chief Conductor Semyon Bychkov has chosen two composers who are very close to him musically for the April subscription week. Beethoven and Brahms also have something in common in their style, as can be seen from the programme combining the piano concerto of the former performed by the pianist Steven Osborne and the symphony of the latter.

Programme

Ludwig van Beethoven

Piano Concerto No. 5 in E flat major, Op. 73 “Emperor” (38')

— Intermission —

Johannes Brahms

Symphony No. 4 in E minor, Op. 98 (41')

Performers

Steven Osborne piano

Semyon Bychkov conductor

Czech Philharmonic

Customer Service of Czech Philharmonic

Tel.: +420 227 059 227

E-mail: info@czechphilharmonic.cz

Customer service is available on weekdays from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. Whenever you need to purchase a wheelchair-accessible ticket.

Performers

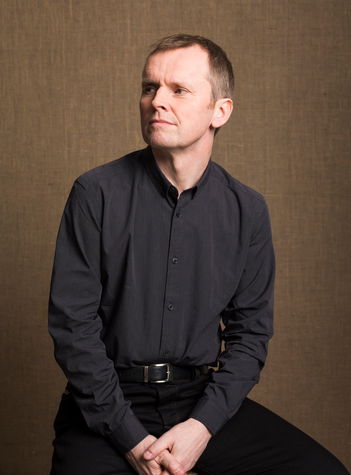

Steven Osborne piano

Described by The Observer as “always a player in absolute service to the composer”, the Scottish native Steven Osborne, an Officer of the Order of the British Empire, is known for his careful reading of musical scores. Osborne’s ability to gain insight into composers’ musical thinking is of benefit to him not only when playing; it has also led him, for example, to publish a new edition of the works of Sergei Rachmaninoff. Still, this approach to interpretation does not at all hinder his experiencing music in a personal way. He is in fact convinced that “Music can’t say anything without us. The way that music speaks through us is that we bring our own emotions to it.”

Critics most recently acclaimed this rare combination of spontaneity with detailed study of the musical sources after hearing Osborne’s recording of Beethoven’s late piano sonatas released on the Hyperion label. Over 25 years, Osborne’s more than 30 CDs for Hyperion ranging from Beethoven to Crumb have earned him many prizes from around the world (including a BBC Music Magazine Award and two Gramophone Awards). He appears on stage giving solo recitals (at such venues as the Lincoln Center and Wigmore Hall, where he has also served as an artist-in-residence) and in collaboration with such orchestras as the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic, the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, the Oslo Philharmonic, the Israel Philharmonic, and the Seattle Symphony Orchestra. Although we have been hearing him play Beethoven or Debussy most frequently in recent years, he opened the current season with the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra playing a piano concerto by Ryan Wigglesworth. He does not hesitate to improvise at his concerts, demonstrating, among other things, his great love of jazz. That is one reason why he has prepared for the current season a special recital programme consisting of miniatures ranging from Bach to jazz.

Besides giving concerts, he is often invited to music festivals such as DeSingel in Antwerp, the Lammermuir Festival, and the Bath International Music Festival, and he devotes himself to teaching at the Royal Academy of Music and the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, where he was born 53 years ago. He is said to have been drawn magnetically to the piano at an early age, and his first steps each morning upon waking always took him to the instrument. It was a natural choice for him to study at St Mary’s Music School in Edinburgh under the guidance of Richard Beauchamp, but even while later studying at the Royal Northern College of Music in Manchester, where his teacher was Renna Kellaway, he claims not to have foreseen a career as a famous; for Osborne, playing was a basic need for life. His breakthrough into the music world came with victory at the Clara Haskil Competition in 1991 followed by first prize at the Naumburg International Competition. Since then, he has risen ever higher.

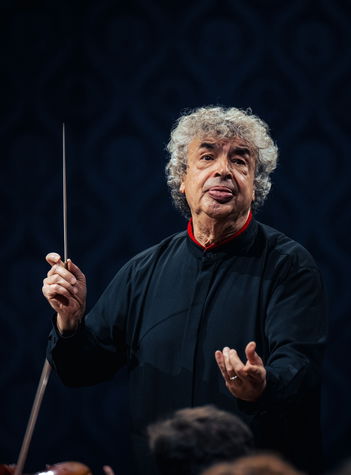

Semyon Bychkov conductor

In addition to conducting at Prague’s Rudolfinum, Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic in the 2023/2024 season, took the all Dvořák programmes to Korea and across Japan with three concerts at Tokyo’s famed Suntory Hall. In spring, an extensive European tour took the programmes to Spain, Austria, Germany, Belgium, and France and, at the end of year 2024, the Year of Czech Music culminated with three concerts at Carnegie Hall in New York.

Among the significant joint achievements of Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic is the release of a 7-CD box set devoted to Tchaikovsky’s symphonic repertoire and a series of international residencies. In 2024, Semjon Byčkov with the Czech Philharmonic concentrated on recording Czech music – a CD was released with Bedřich Smetanaʼs My Homeland and Antonín Dvořákʼs last three symphonies and ouvertures.

Bychkovʼs repertoire spans four centuries. His highly anticipated performances are a unique combination of innate musicality and rigorous Russian pedagogy. In addition to guest engagements with the world’s major orchestras and opera houses, Bychkov holds honorary titles with the BBC Symphony Orchestra – with whom he appears annually at the BBC Proms – and the Royal Academy of Music, who awarded him an Honorary Doctorate in July 2022. Bychkov was named “Conductor of the Year” by the International Opera Awards in 2015 and, by Musical America in 2022.

Bychkov began recording in 1986 and released discs with the Berlin Philharmonic, Bavarian Radio, Royal Concertgebouw, Philharmonia Orchestra and London Philharmonic for Philips. Subsequently a series of benchmark recordings with WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne featured Brahms, Mahler, Rachmaninov, Shostakovich, Strauss, Verdi, Glanert and Höller. Bychkov’s 1993 recording of Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin with the Orchestre de Paris continues to win awards, most recently the Gramophone Collection 2021; Wagner’s Lohengrin was BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Year (2010); and Schmidt’s Symphony No. 2 with the Vienna Philharmonic was BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Month (2018).

Semyon Bychkov has one foot firmly in the culture of the East and the other in the West. Born in St Petersburg in 1952, he studied at the Leningrad Conservatory with the legendary Ilya Musin. Denied his prize of conducting the Leningrad Philharmonic, Bychkov emigrated to the United States in 1975 and, has lived in Europe since the mid-1980’s. In 1989, the same year he was named Music Director of the Orchestre de Paris, Bychkov returned to the former Soviet Union as the St Petersburg Philharmonic’s Principal Guest Conductor. He was appointed Chief Conductor of the WDR Symphony Orchestra (1997) and Chief Conductor of Dresden Semperoper (1998).

Compositions

Ludwig van Beethoven

Piano Concerto No. 5 in E flat major, Op. 73 “Emperor”

Wartime circumstances also influenced the other work on today’s programme. Beethoven composed his Piano Concerto in E flat major, Op. 73, his fifth and final work in the genre, in the spring of 1809 as Napoleon’s troops were marching on Vienna. By May, Austria’s imperial capital was under siege by the French army. Ludwig van Beethoven (1770‒1827) endured the ensuing bombardment in the cellar of the house of his brother Kaspar. After several months of siege and the Battle of Wagram, the Austrian army capitulated in October 1809, and an armistice was signed. Beethoven then took advantage of the opportunity to depart from Vienna, but he soon began to miss his supporters and patrons. He wanted to present new compositions to them including the Piano Concerto in E flat major, which he dedicated to Archduke Rudolf, the younger brother of Emperor Francis I. The archduke was Beethoven’s pupil and his supporter for many years.

As it turned out, the concerto had to wait two years for its premiere, in part because Beethoven’s progressing deafness left him unable to play the solo part himself. In the end, the premiere took place in Leipzig, and the soloist was Friedrich Schneider. The most important performance of the concerto for Beethoven was given before the Viennese public on 15 February 1812 at the Theater am Kärntnertor. Playing the solo part was the youthful but already well known pianist Carl Czerny, a pupil of Beethoven and one of his most faithful followers. The word “Emperor” was not originally part of the title—it was probably added by the publisher Johann Baptist Cramer, possibly because of the original dedication to a member of the royal family.

The composition is the most symphonic of all of Beethoven’s concertos, with the orchestra serving not merely as the accompaniment, but instead as a full-fledged partner. While the orchestra can exchange roles with the virtuosic piano part, it can also play a hushed accompaniment beneath piano passages or exhibit tenderness in the middle movement. Sophistication of orchestration is especially apparent in the use of the woodwinds and horns. Beethoven entrusts the soloists with a wide range of technical challenges as well as with beautiful themes that he develops with true mastery. In doing so, he employs the broader canvas available to the piano in this concerto compared with his sonatas or chamber works. This can be seen, for example, in the main theme of the concluding third movement, a grand and exuberant allegro in rondo form.

Johannes Brahms

Symphony No. 4 in E minor, Op. 98

Johannes Brahms, a native of the north-German city Hamburg, settled in Vienna permanently in 1863, where he was offered the position of choirmaster of the Wiener Singakademie, but after about a year he resigned from the position to devote himself fully to composing. The conductor and composer Hans von Bülow and Clara and Robert Schumann were among his life-long friends, and it was Robert Schumann who declared that Brahms was the long-awaited successor to Ludwig van Beethoven. Brahms is generally regarded as having brought to its apex the compositional style that Beethoven had begun, especially in the field of the symphony. However, Brahms was also thoroughly familiar with the works of Mozart, Haydn, Johann Sebastian Bach, and Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy. The music of all of these great masters inspired Brahms, especially with respect to mastery of classical musical form, which was of key importance for his musical expression. It was because of Brahms’s respect for tradition that his music was seen as being in opposition to the progressive approach of the operatic genius Richard Wagner or to the new genre of the symphonic poem introduced by Franz Liszt. However, the notorious “War of the Romantics” was fought much less between the composers themselves than between music theorists who often vehemently defended one side or the other. History, however, showed that both sides of the War of the Romantics were equally important for music’s future development. For example, the leader of the Second Viennese School Arnold Schoenberg proudly claimed himself to be an admirer of and successor to Brahms.

Nothing terrified Brahms more than being compared with Beethoven. Concerning Beethoven, Brahms wrote in a letter to the conductor Hermann Levi: “I shall never write a symphony! You have no idea what it’s like to hear the heavy footsteps of a giant like him behind you!“ As it turned out, Brahms wrote four symphonies, and today they are all an integral part of the standard symphonic repertoire. The composer’s journey to writing his First Symphony was especially difficult. Fourteen years separate the first version of the manuscript, which he sent to Clara Schumann in 1862, and the premiere of the completed symphony. Brahms wrote his next three symphonies noticeably more quickly. After the last one, the Symphony No. 4 in E minor, with the exception of the Double Concerto for violin and cello, he turned away entirely from composing for orchestra, thereafter devoting himself only to writing songs and music for chamber ensembles.

Brahms’s last symphony was premiered in October 1885, and unlike the two before it, Brahms decided to have the Fourth premiered away from Vienna. This took place in the German city Meiningen, and Brahms himself conducted the local court orchestra, of which Hans von Bülow was the music director at the time. The public in Meiningen was enthusiastic, but the Viennese public less so; ultimately, the symphony won over the Viennese as well. Of all of Brahms’s symphonies, it is the Fourth that refers back to Beethoven the most, and at the same time, it is a perfect example of how eloquently absolute music can speak. It has no programmatic content, but many music theorists still regard it as a work of exceptional intellectual seriousness and as one of the most tragic symphonies in the history of the entire genre. The American musicologist Jan Swafford went so far as to declare: “The E Minor ‘means’ many things, but surely part of it is this: his funeral song for his heritage, for a world at peace, for an Austro-German middle class that honoured and understood music like no other culture, for the sweet Vienna he knew, for his own lost loves. In one of the last pieces he wrote in 1896, Brahms would set the E Minor Symphony’s first four notes, B G E C to the words ‘O death, O death!’” Adding to the whole work’s gloomy, even tragic mood is the home key of E minor, which predominates throughout, and unlike in previous symphonies by Brahms and his predecessors, the music does not modulate to the brighter, more optimistic major mode even at the end. The symphony is also remarkable for the economy of musical resources that Brahms employs to construct such a magnificent work; for example, the first movement is based in its entirety on the opening two-note motif. The middle movements, Andante and Allegro giocoso, reveal both Brahms’s feeling for songful lyricism and his sophisticated, playful handling of rhythm. The concluding fourth movement is remarkable not only for its minor-key ending, but especially for having been composed in the form of a passacaglia. The form, originally from the baroque era, is based on a repeating theme, usually in the bass, above which the composer creates one new contrapuntal variation after another. “The conclusion of this movement, searingly, crushingly tragic, is a veritable orgy of destruction, a terrible counterpart to the paroxysm of joy at the end of Beethoven’s last symphony”, wrote the conductor Felix Weingartner in 1909 about Brahms’s very last symphonic movement.