1 / 6

Czech Philharmonic • Zagreb

To Zagreb, the Czech Philharmonic and its chief conductor Semyon Bychkov are taking two ballet suites by Béla Bartók and Igor Stravinsky. The soloist in a brand new piano concerto by Thierry Escaich will be the Korean pianist Seong-Jin Cho.

Programme

Béla Bartók

The Miraculous Mandarin, suite from the ballet-pantomime (20')

Thierry Escaich

Etudes symphoniques for piano and orchestra (30')

— Intermission —

Igor Stravinsky

Petrushka. Burlesque scenes in four tableaux (1947 concert version) (34')

Performers

Seong-Jin Cho piano

Semyon Bychkov conductor

Czech Philharmonic

To purchase online, visit the event presenter's website.

Performers

Seong-Jin Cho piano

With an innate musicality and overwhelming talent, Seong-Jin Cho has established himself worldwide as one of the leading pianists of his generation and most distinctive artists on the current music scene. His thoughtful and poetic, assertive and tender, virtuosic and colourful playing can combine panache with purity and is driven by an impressive natural sense of balance.

Seong-Jin Cho was brought to the world’s attention in 2015 when he won First Prize at the Chopin International Competition in Warsaw, and his career has rapidly ascended since. In January 2016, he signed an exclusive contract with Deutsche Grammophon. An artist high in demand, Cho works with the world's most prestigious orchestras including Berliner Philharmoniker, Wiener Philharmoniker, London Symphony Orchestra, Orchestre de Paris, New York Philharmonic and The Philadelphia Orchestra. Conductors he regularly collaborates with include Myung-Whun Chung, Gustavo Dudamel, Yannick Nézet-Séguin, Andris Nelsons, Gianandrea Noseda, Sir Simon Rattle, Santtu Matias Rouvali and Esa-Pekka Salonen.

An active recitalist very much in demand, Seong-Jin Cho performs in many of the world’s most prestigious concert halls. During the coming season he is engaged to perform solo recitals at the likes of Carnegie Hall, Boston Celebrity Series, Walt Disney Hall, Alte Oper Frankfurt, Liederhalle Stuttgart, at Laeiszhalle Hamburg, Berliner Philharmonie, Musikverein Wien and he debuts in recital at the Barbican London.

Seong-Jin Cho’s recordings have garnered impressive critical acclaim worldwide. The most recent one is of Chopin’s Piano Concerto No. 2 and Scherzi with the London Symphony Orchestra and Gianandrea Noseda, having previously recorded Chopin’s Piano Concerto No. 1 as well as the Four Ballades with the same orchestra and conductor. His latest solo album titled The Wanderer was released in May 2020.

Born in 1994 in Seoul, Seong-Jin Cho started learning the piano at the age of six and gave his first public recital aged 11. In 2009, he became the youngest-ever winner of Japan’s Hamamatsu International Piano Competition. In 2011, he won Third Prize at the International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow at the age of 17. From 2012–2015 he studied with Michel Béroff at the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique de Paris. Seong-Jin Cho is now based in Berlin.

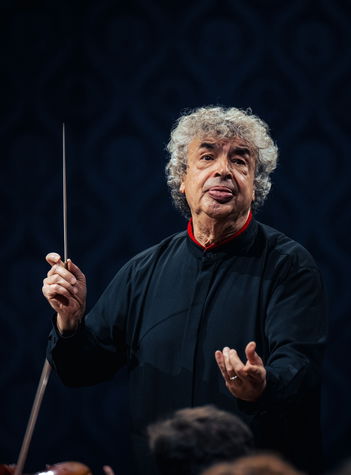

Semyon Bychkov conductor

In addition to conducting at Prague’s Rudolfinum, Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic in the 2023/2024 season, took the all Dvořák programmes to Korea and across Japan with three concerts at Tokyo’s famed Suntory Hall. In spring, an extensive European tour took the programmes to Spain, Austria, Germany, Belgium, and France and, at the end of year 2024, the Year of Czech Music culminated with three concerts at Carnegie Hall in New York.

Among the significant joint achievements of Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic is the release of a 7-CD box set devoted to Tchaikovsky’s symphonic repertoire and a series of international residencies. In 2024, Semjon Byčkov with the Czech Philharmonic concentrated on recording Czech music – a CD was released with Bedřich Smetanaʼs My Homeland and Antonín Dvořákʼs last three symphonies and ouvertures.

Bychkovʼs repertoire spans four centuries. His highly anticipated performances are a unique combination of innate musicality and rigorous Russian pedagogy. In addition to guest engagements with the world’s major orchestras and opera houses, Bychkov holds honorary titles with the BBC Symphony Orchestra – with whom he appears annually at the BBC Proms – and the Royal Academy of Music, who awarded him an Honorary Doctorate in July 2022. Bychkov was named “Conductor of the Year” by the International Opera Awards in 2015 and, by Musical America in 2022.

Bychkov began recording in 1986 and released discs with the Berlin Philharmonic, Bavarian Radio, Royal Concertgebouw, Philharmonia Orchestra and London Philharmonic for Philips. Subsequently a series of benchmark recordings with WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne featured Brahms, Mahler, Rachmaninov, Shostakovich, Strauss, Verdi, Glanert and Höller. Bychkov’s 1993 recording of Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin with the Orchestre de Paris continues to win awards, most recently the Gramophone Collection 2021; Wagner’s Lohengrin was BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Year (2010); and Schmidt’s Symphony No. 2 with the Vienna Philharmonic was BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Month (2018).

Semyon Bychkov has one foot firmly in the culture of the East and the other in the West. Born in St Petersburg in 1952, he studied at the Leningrad Conservatory with the legendary Ilya Musin. Denied his prize of conducting the Leningrad Philharmonic, Bychkov emigrated to the United States in 1975 and, has lived in Europe since the mid-1980’s. In 1989, the same year he was named Music Director of the Orchestre de Paris, Bychkov returned to the former Soviet Union as the St Petersburg Philharmonic’s Principal Guest Conductor. He was appointed Chief Conductor of the WDR Symphony Orchestra (1997) and Chief Conductor of Dresden Semperoper (1998).

Compositions

Béla Bartók

The Miraculous Mandarin, suite from the ballet-pantomime

The Hungarian composer Béla Bartók was born in the town Nagyszentmiklós, today Sânnicolau Mare, Romania. He received musical training in Pozsony, today Bratislava, and at the Academy of Music in Budapest. He established himself successfully as a concert pianist and soon began teaching piano himself at the academy in Budapest. Bartók also got off to a promising start as a composer when the conductor Hans Richter led performances of his early symphonic poem Kossúth in Budapest and Manchester.

Hungarian folk music became a powerful source of inspiration for Bartók. He was aware that many supposedly Hungarian folk songs were actually popular songs written to imitate folk music. In those days, the brilliant music of gypsy bands also greatly distorted people’s ideas about what Hungarian music had originally been like. It was necessary to visit the most remote rural areas of Hungary, Romania, Slovakia, Bulgaria, the Carpathians, and Danubian Wallachia, where one could find and systematically record folk music in its authentic form. And that is just what Bartók did: he made recordings on phonograph cylinders and notated what he heard, then at home he subjected his findings to scholarly study and published collected editions of the songs. As a folklorist, he earned an international reputation as an authority. Even more importantly, however, he was able to carry over all of those limping rhythms, unmelodious melodies, and inharmonious harmonies into his own composing, just as Leoš Janáček did on a more modest scale in this country.

Bartók’s stage works all take inspiration from loneliness, conflict in the relations between men and women, and aversion to the cruelty of the modern world. The stage trilogy begins in 1911 with the one-act opera Bluebeard’s Castle, followed six years later by the ballet The Wooden Prince, which incidentally shares a motif in common with Stravinsky’s Petrushka: a wooden marionette as the central character. The cycle climaxes with the ballet pantomime The Miraculous Mandarin, a wild, unadorned portrayal of the baseness, primitivism, and brutality of human nature. The scenario is played out entirely in the spirit of Expressionism, a European artistic movement that emerged from the tragedy of the First World War and dominated the arts on the continent, including music.

The Miraculous Mandarin is a story about the life-giving power of love ruined by inhumaneness. The work was written in 1918, but until 1924 it remained in the form of a reduction for piano four-hands. Under the clerical authoritarian regime of Horthy’s Hungary, where Bartók definitely did not have things easy, the authorities twice thwarted attempts to have the pantomime performed. Bartók did not finish orchestrating The Miraculous Mandarin until preparations began for the premiere in Cologne, Germany. The performance finally took place on 27 November 1926 with Jenő Szenkár conducting. The audience left in shock, and no more performances were given. The Miraculous Mandarin was banned by the mayor of Cologne, none other than Konrad Adenauer, the future first post-war chancellor of West Germany. He justified the ban on the grounds of “immorality, morbidity of the subject, and political (!) indecency”. No performances of The Miraculous Mandarin were permitted in Hungary until after 1945. Bartók’s work was not fully rehabilitated in his homeland until 1956, eleven years after the great composer’s death in New York.

The action of the ballet pantomime is based on a story by Melchior Lengyel that was very controversial in its day. We are taken to a dark lair in an unnamed metropolis in the West, where three criminals are operating a well-established business: with the aid of a young prostitute, they lure wealthy johns into the flat, where they rob and murder them. The girl lures in two men, one after the other, but neither has any money, so they are “only” beaten and unceremoniously thrown out. The third man to enter is the mysterious central character, a foreigner dressed as a Chinese mandarin, who at first seems to be indifferent to the girl’s feigned feelings. The prostitute therefore tries her best to seduce him until she actually awakens wild passion of unusual force in him. When the mandarin—like other unfortunate men before him—is murdered by the three ruffians, he is brought back to life miraculously by the power of his suddenly awakened love. The same thing is repeated after a second attempted murder, when the Chinese man, spattered with his own blood, again rises and professes his love for the prostitute. Only then does the girl understand that the mandarin will not finally die until after a kiss in her embrace. Once that take place, the ballet ends with a third, successful murder of the main character.

The orchestral suite from the ballet The Miraculous Mandarin is captivating mainly because of its fiery, pulsating rhythms. Often, Bartók intentionally allows the level of lyrical warmth to approach absolute zero. Powerful moments are amplified by explosive dynamics, shifting accents, vigorous tremolos, expressive sighs, wild trills, and barbaric fast passages. There is a lack of sustained, memorable melodic themes; in spite of this, the music is wonderful, seldom giving listeners a chance to catch their breath.

Thierry Escaich

Études symphoniques for piano and orchestra

The composer, organist, and improviser Thierry Escaich is a prominent figure in the world of contemporary music and one of the most important French composers of his generation. His three artistic roles are intertwined and enable him to work as a creator, performer, and artistic collaborator. He was born in Nogent-sur-Marne near Paris, and he graduated from the organ, improvisation, and composition departments of the Paris Conservatoire, where he won First Prize eight times, and where he has been teaching improvisation and composition since 1992. In 1996 he was appointed the church organist at Saint-Étienne-du-Mont in Paris as a successor of the great Maurice Duruflé. Several times in his career, he has accepted the position of artist- or composer-in-residence with the Orchestre national de Lyon, the Orchestre national de Lille, the Orchestre de chambre de Paris, and at present the Dresden Philharmonic.

Escaich’s works are performed by leading orchestras and chamber ensembles of Europe and North America. They are in the repertoire of such important artists as Lisa Batiashvili, François Leleux, Paavo Järvi, Alan Gilbert, Alain Altinoglu, Renaud Capuçon, Gautier Capuçon et al. Escaich’s music has been honoured with prizes at the Victories de la Musique five times (in 2003, 2006, 2011, 2017, and 2022). Escaich’s CD recordings have won many more awards. In 2013, the composer was admitted to the Académie des beaux-arts in Paris, a prestigious institution with the goal of promoting artistic creation and protecting France’s cultural heritage.

Escaich has written many of his compositions for organ, performing them on his own recitals. These works are also played by other organists around the world. Opera is another important field of Escaich’s activity. He wrote his first opera Claude in 2013 for the theatre in Lyon, followed in 2021 by the opera Point dʼorgue commissioned by the Opéra national de Bordeaux. The world premiere of Escaich’s latest opera Shirine took place in May 2022, again at the Opéra de Lyon. His orchestral works include the Chaconne for orchestra, the Symphony No. 1 (Kyrie d'une messe imaginaire), the Concerto for Orchestra (Symphony No. 2), the oratorio Le Dernier Évangile, and most recently a work titled Ritual Opening for a festival in Rotterdam in 2019. Outstanding examples of his numerous works for solo instrument and orchestra include the Viola Concerto “La Nuit des chants” for Antoine Tamestit, three concertos for organ and orchestra, and most recently concertos for flute (premiered on 5 March 2021 at the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam) and guitar (premiered on 30 January 2022 in Chambéry). Escaich also writes chamber music and film scores, such as music for new restorations of the famous silent films Phantom of the Opera and Metropolis.

Semyon Bychkov has commissioned Études symphoniques for piano and orchestra for the Czech Philharmonic. The cycle of four studies integrates various forms of dialogue between the soloist and the orchestra, which sometimes play very closely together, while at other times they engage in a polyphony of opposites or even contrast sharply with each other. In the ethereal atmosphere of the opening motif, the listener easily recognises a reminiscence of J. S. Bach, which recurs in various guises throughout the composition.

The opening movement, Dérives, is a passacaglia derived from the motif mentioned above. The piano plays arpeggios depicting neo-Baroque arabesques and tries to get the music moving towards more syncopated, dance-like episodes, but it is relentlessly interrupted by the passacaglia, which constantly returns the movement to its original mood. Furtif begins as a lively, playful scherzo interrupted by mysterious modal melodies, which attempt to assert themselves against the increasingly violent, relentless scherzo, leading to a touch of jazz in which the piano seems to be improvising in the refrain. In the third movement, Mirage, there is again an alternation between an ecstatic world, in which melodic lines are interwoven into many canons in a clear and calm harmonic universe, and a more lyrical motif dramatically emphasised by repeated notes in the piano. The bubbling waves are interrupted by snippets of romantic phrases, perhaps coming from somewhere in the distant past, and the resultant duality builds to a climax in a wild waltz. After a short episode, when piano ornaments weave their way around a trumpet melody in a nocturnal reminiscence of the beginning of the whole composition, the concluding Toccata ushers in more rhythmic staccato music with increasing dynamics, seeming to continue what has already been suggested in the second movement. It is only the return of the opening chordal leitmotif that contradicts the energetic jubilation by bringing in more tragic tones.

Igor Stravinsky

Petrushka. Burlesque scenes in four tableaux

The history of the ballet Petrushka begins on 10 January 1910 in Saint Petersburg. The orchestra of the Imperial Theatre gave the premiere of Fireworks, a work by Igor Stravinsky, still an unknown novice composer at the time. Sitting in the audience was Serge Diaghilev, an impresario who organised concerts series of Russian music in Paris. In 1909 he took an entire Russian ballet troupe to the French capital and turned them into prestigious Ballets Russes. In Stravinsky’s Fireworks, Diaghilev sensed the emergence of a new style of Russian music that might resonate in the future in the modern, cosmopolitan West. Stravinsky, a law school graduate from a prominent family, had so far produced no more than a handful of compositions and had taken private compositions lessons from Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. Diaghilev recognised the strength of Stravinsky’s talent and offered him the chance to collaborate on a ballet based on the Russian fairy tale The Firebird. The very successful premiere took place that same year at the Opéra national de Paris.

It was clear that this mutually beneficial cooperation with the Ballets Russes should be continued. Meanwhile, Stravinsky, who was dividing his time between Paris, Switzerland, and Saint Petersburg, had begun work on a new piano concerto. Diaghilev persistently persuaded him to recast the partially finished work into the form of a new ballet for the 1911 season of the Ballets Russes. And he succeeded, resulting in the creation of Petrushka. Stravinsky collaborated with Alexander Benois on the scenario for the new ballet, and the plot is simple. We are taken to a Russian fair (which Benois places in Saint Petersburg’s Admiralty Square), where a puppeteer at a street theatre is presenting three marionettes: the clown Petrushka, a ballerina, and a jealous Moor. Petrushka, a symbol of those who have been wronged, falls in love with the ballerina, but she prefers the brutish, manly Moor. Petrushka, a gentle, poetic being, contends for her in vain, but he is humiliated and driven away. He finally succumbs when the Moor stabs him with his sabre in cold blood. This killing, an act of savage violence, shocks everyone in attendance; the crowd breaks up, and the puppeteer drags Petrushka from the stage. Suddenly, the clown’s ghost appears above the entrance to the little theatre and thumbs his nose, driving the terrified puppeteer or charlatan away from the stage once and for all. Feeling and love are triumphant, at least morally, over brutality and primitivism.

The action of the ballet is enlivened by picaresque carnival figures, excited farmers, coachmen, street vendors, a peasant with a dancing bear, wandering musicians, and bizarre masqueraders who look like they come from one of the early paintings by another Russian who had arrived in Paris at the time, Moishe Shagal, later known as Marc Chagall. The ballet is conceived as “burlesque scenes” in the style of kitschy, colourful Russian carnival prints called lubki. Stravinsky does not hesitate to give musical depictions of a barrel organ, a music box, an accordion, the cries of street vendors, and puppeteers summoning their audience. He shamelessly quotes even the most banal Russian ditties like “She Had a Wooden Leg”. The innovative harmony of Petrushka has its roots in bitonal elements (the clown’s fanfare simultaneously in C major and F sharp major). The orchestration is brimming with colour and novel ideas. There is also a delightful stylisation of a waltz in the style of Lanner. From the beginning, the piano plays a very important role in the orchestra, but its significance is gradually diminished, corresponding to the process of recasting the intended piano concerto into the form of a ballet. Petrushka was written in the Swiss towns Clarens and Lausanne and was completed in Beaulieu-sur-Mére near Nice on the Côte d'Azur. A direct result of this strenuous work was nicotine poisoning from Stravinsky’s excessive smoking; he had to undergo treatment in hospital.

Taking part at the first Parisian production of Petrushka were a number of other important figures who contributed greatly to the overall success. Besides Diaghilev, these included the wonderful choreographer of the Ballets Russes Michel Fokine, the conductor Pierre Monteux, and above all the legendary dancers Vaslav Nijinsky and Tamara Karsavina. Nijinsky’s portrayal of the role of Petrushka became the unattainable model for whole generations of successors. The premiere on 13 June 1911 at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris was a triumph. Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring followed two years later. It work caused a scandal, but that is another story…

In the summer of 1921, Stravinsky arranged three sections of the ballet Petrushka for solo piano at the request of the virtuoso Arthur Rubinstein (Three Movements from Petrushka). In 1947, Stravinsky revised the whole score for concert performances. Today, the half-hour ballet is played in its entirety, so this is not a ballet suite in the usual sense.