1 / 6

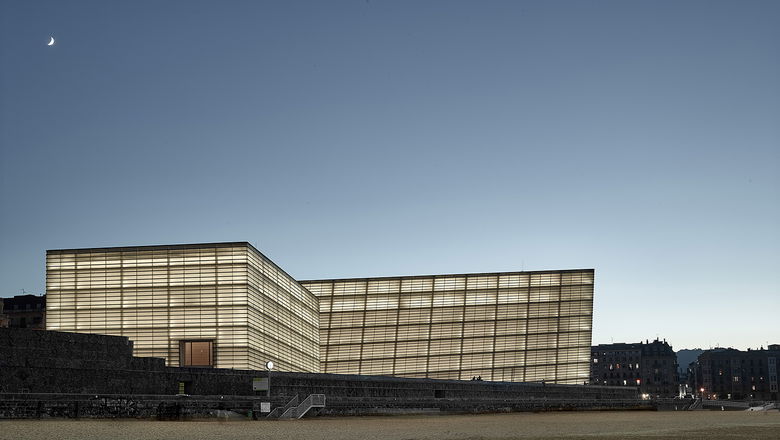

Czech Philharmonic • San Sebastián

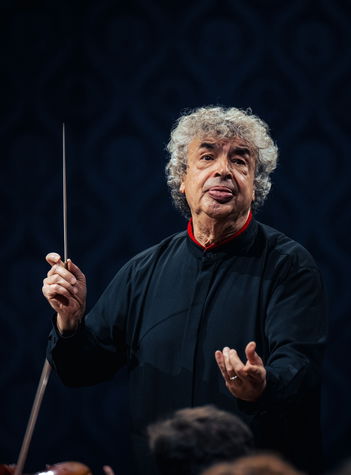

Mahler’s symphonies appear not only in the recording schedule of the Czech Philharmonic or in its Prague season, but also on tour. They will perform the Seventh Symphony, which is associated with Prague. Leading the top Czech orchestra will be its chief conductor Semyon Bychkov.

Programme

Gustav Mahler

Symphony No. 7 in E minor

Performers

Semyon Bychkov conductor

To purchase online, visit the event presenter's website.

Performers

Semyon Bychkov conductor

In addition to conducting at Prague’s Rudolfinum, Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic in the 2023/2024 season, took the all Dvořák programmes to Korea and across Japan with three concerts at Tokyo’s famed Suntory Hall. In spring, an extensive European tour took the programmes to Spain, Austria, Germany, Belgium, and France and, at the end of year 2024, the Year of Czech Music culminated with three concerts at Carnegie Hall in New York.

Among the significant joint achievements of Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic is the release of a 7-CD box set devoted to Tchaikovsky’s symphonic repertoire and a series of international residencies. In 2024, Semjon Byčkov with the Czech Philharmonic concentrated on recording Czech music – a CD was released with Bedřich Smetanaʼs My Homeland and Antonín Dvořákʼs last three symphonies and ouvertures.

Bychkovʼs repertoire spans four centuries. His highly anticipated performances are a unique combination of innate musicality and rigorous Russian pedagogy. In addition to guest engagements with the world’s major orchestras and opera houses, Bychkov holds honorary titles with the BBC Symphony Orchestra – with whom he appears annually at the BBC Proms – and the Royal Academy of Music, who awarded him an Honorary Doctorate in July 2022. Bychkov was named “Conductor of the Year” by the International Opera Awards in 2015 and, by Musical America in 2022.

Bychkov began recording in 1986 and released discs with the Berlin Philharmonic, Bavarian Radio, Royal Concertgebouw, Philharmonia Orchestra and London Philharmonic for Philips. Subsequently a series of benchmark recordings with WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne featured Brahms, Mahler, Rachmaninov, Shostakovich, Strauss, Verdi, Glanert and Höller. Bychkov’s 1993 recording of Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin with the Orchestre de Paris continues to win awards, most recently the Gramophone Collection 2021; Wagner’s Lohengrin was BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Year (2010); and Schmidt’s Symphony No. 2 with the Vienna Philharmonic was BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Month (2018).

Semyon Bychkov has one foot firmly in the culture of the East and the other in the West. Born in St Petersburg in 1952, he studied at the Leningrad Conservatory with the legendary Ilya Musin. Denied his prize of conducting the Leningrad Philharmonic, Bychkov emigrated to the United States in 1975 and, has lived in Europe since the mid-1980’s. In 1989, the same year he was named Music Director of the Orchestre de Paris, Bychkov returned to the former Soviet Union as the St Petersburg Philharmonic’s Principal Guest Conductor. He was appointed Chief Conductor of the WDR Symphony Orchestra (1997) and Chief Conductor of Dresden Semperoper (1998).

Compositions

Gustav Mahler

Symphony No. 7 in E minor

“… the Seventh is too complicated for a public that knows nothing about me.”

In 1908 from May until October, a grandiose event was taking place in Prague on the occasion of the 60th anniversary of the reign of Emperor Franz Joseph I: the Jubilee Exhibition of the Chamber of Commerce and Trade. At the exhibition, the Czech lands presented themselves as the industrial heart of the monarchy. After all, Czech territory boasted, for example, the largest sugar refinery, distillery, and machine works anywhere in Austria-Hungary, as well as the largest mill or coal mine. However, the organisers and visitors paid even greater attention to cultural events including music. Various musical productions were taking place each day at Prague’s Exhibition Grounds both indoors and outdoors. The generous scale of the exhibition remains impressive to this day. For example, an enormous concert pavilion was built at the Prague Exhibition Grounds (it was demolished after the exhibition). The opening concert took place there on 25 May 1908 with works by Ludwig van Beethoven, Richard Wagner, and Bedřich Smetana. Gustav Mahler conducted the Exhibition Orchestra consisting of players from the Czech Philharmonic and the New German Theatre. Then on 19 September 1908 at the same venue with the same orchestra, this time expanded to 100 players, Mahler gave the world premiere of his Seventh Symphony.

It was not by chance that Gustav Mahler (1860–1911) gave the first performance of his Symphony No. 7 in Prague. A native of Kaliště, a little Czech village near Humpolec, he had strong personal and professional ties to the Czech lands. Now in 1908 he was coming to Prague as a world-famous artist—a conductor and a composer. He was exceptionally predisposed for those activities, but he was always so consumed by each of them that he was unable to devote himself to both at the same time. As a composer, he did not have to deal with the operational issues that weighed upon him in the conducting profession, which usually involved the position of director of an opera house. However, devoting himself exclusively to composing probably would not have been right for him either. He had become increasingly aware of “the need for practical activity as a counterweight to the tremendous inner turmoil felt while composing.” On the other hand, he had less time for composing than he would have liked; he had become a summer holiday composer. Two years before his death, he mentioned this characteristically in a letter at the end of the summer: “Sadly, summer holiday is coming to an end, so I am in an annoying situation—as usual, once again this time—still out of breath, I have to leave my paper behind, return to the city and go to work. I guess that is my destiny.” Mahler implemented his standard model of spending his summers working beside Alpine lakes in 1893, and he maintained that routine for the rest of his life. First, he made visits to Attersee in Upper Austria, then from 1900 he went to Wörthersee in Carinthia.

Of Gustav Mahler’s nine finished symphonies, the Symphony No. 7 in E minor (1904–1905) is usually regarded as the strangest and most mysterious. In its five movements, the composer ventures into the mysterious and frightening world of the night, where reality confronts dreams, and where it is difficult to differentiate fact from delusions or sincerity from irony. To express the alienation of mankind, the composer uses the most modern language with raw, merciless dissonances and unpredictable modulations. In addition, the Seventh is less unified than Mahler’s previous symphonies. Unusually, he wrote it in two phases. While Mahler was envisioning the conclusion of the Sixth Symphony in the summer of 1904, two more themes occurred to him, and at first, he just jotted them down, but right after having finished the Sixth, he made continuous sketches of two independent movements that he called “Nachtmusik” (“Night Music”). The next summer, he wanted to build upon the two already drafted movements, but it took a long time for him to find inspiration. Later, he reminisced about that summer in a letter to his wife Alma: “For 14 days I was suffering to the point of dejection, as you surely recall, until I returned to the Dolomites! There, the same thing repeated itself, and finally I gave up and returned home, convinced that the summer was wasted. In Krumpendorf […] I got into a boat to be ferried to the other side of the water. Upon the first stroke of the oars, the theme occurred to me (or rather its rhythm and character) for the opening of the first movement—and in four weeks I had completely finished the first, third, and fifth movements.”

The monumental first movement might be the most modern music that Mahler ever composed. During the rehearsals, the composer described it as “a tragic night without stars or moonlight”, full of “raging, grim, cruel, and tyrannical forces” that are ruled “by the power of darkness”. A tenor horn solo right at the beginning announces: “I am the master here! I will impose my will!” The title of the second movement, “Night Music”, might evoke the mild image of a gallant serenade, but that is not the case with Mahler, as Leonard Bernstein clearly explained: “The minute we understand that the word Nachtmusik does not mean nocturne in the usual lyrical sense, but rather nightmare—that is, night music of emotion recollected in anxiety instead of tranquillity—then we have the key to all this mixture of rhetoric, camp, and shadows.” The following Scherzo marked Schattenhaft (shadowy) is also ghostly in mood. (Many years later, Dmitri Shostakovich wrote music in a similarly sarcastic vein, brilliantly following in the footsteps of Mahler, whom he admired.) Like the second movement, the fourth is also called “Night Music”, but it is very different in character and much more intimate. According to Alma, in this movement Mahler “had visions in the manner of Eichendorff in mind, with the murmuring of springs and German Romanticism.” The orchestra is suddenly reduced drastically, down to chamber forces, and the sound of a serenade is suggested by guitar and mandolin. But let us not be misled. This is not a real serenade, but one with demons flickering past. The final movement returns to the daylight with all of its majesty and jubilant spectacle. Is this nothing but irony and humour, a postmodern collage? Mahler certainly never wrote a more provocative ending to any of his other symphonies. After having finished his Seventh, the composer expected the public’s reaction to be one of confusion. For this reason, he did not rush to have the work played.

“My symphony will be performed on 19 September [1908] in Prague, but only as long as the Czechs and Germans don’t come to blows”, wrote Mahler to his friend Bruno Walter, referring to the city’s unending ethnic strife. In the Exhibition Orchestra, Czechs and Germans were represented equally. Given the work’s difficult demands, the orchestra had been expanded to a total of 100 players with members of the Czech Philharmonic and of the New German Theatre. Mahler was able to rehearse the orchestra for nearly two weeks, which was very unusual. Still, the composer was quite nervous. After all, the whole orchestra had to be properly prepared to perform an unknown and difficult work. Moreover, during the rehearsals, even in his hotel room the composer was still making changes to the orchestration directly into the orchestral parts. “Mahler was terribly tired,” wrote Alma, recalling those days. “But his condition improved slowly, and he became more confident as the rehearsals progressed.” The first performance turned out to be a success, and for Mahler it meant an unquestionably great personal success. He received support and congratulations mainly from musicians who, like Mahler, were pushing the limits of what was possible (Schoenberg, Berg). And some lukewarm reactions were unsurprising. After all, Mahler was very well aware that his time was yet to come, and he maintained a healthy outlook. Although the Seventh was performed several times the following year with great success in the Netherlands, he decided that in New York he would “begin with the First, so the Seventh will only come later on because the Seventh is too complicated for a public that knows nothing about me.”