1 / 6

Czech Philharmonic • Edinburgh

At the first performance, the leading Czech orchestra will present itself in an all-Czech programme. Dvořák’s energetic Carnival Overture will be followed by Bohuslav Martinů’s original Concerto for Two Pianos and Orchestra played by the Labèque sisters and Leoš Janáček’s magnificent Glagolitic Mass with Czech soloists and a Scottish choir.

Programme

Antonín Dvořák

Carnival Overture, Op. 92

Bohuslav Martinů

Concerto for Two Pianos and Orchestra, H 292

Leoš Janáček

Glagolitic Mass, cantata for soloists, choir, orchestra and organ

Performers

Katia and Marielle Labèque pianos

Evelina Dobračeva soprano

Lucie Hilscherová alto

Aleš Briscein tenor

Jan Martiník bass

Edinburgh Festival Chorus

Aidan Oliver choirmaster

Semyon Bychkov conductor

Czech Philharmonic

To purchase online, visit the event presenter's website.

Performers

Katia & Marielle Labèque pianos

From the Basque region of France, then almost untouched by classical music, to the greatest concert halls in the world – this is the story of the Labèque sisters with a career spanning more than 50 years, who have been described as “the best piano duo in front of an audience today” (New York Times). But the shared story of the sisters, who have had a lifelong and intense relationship both professionally and personally, is much longer. The elder Katia first began playing piano under the tutelage of her mother, a pianist and piano teacher, and two years younger Marielle soon followed suit. In 1968, they entered the Paris Conservatory, but still as two soloists – the idea of forming a piano duo did not arise until after they had graduated from the conservatory, and so they then enrolled in a chamber music class there. They still remember how, while rehearsing Visions de l’Amen, they were suddenly interrupted by Olivier Messiaen, who happened to be passing by their class and wondered who was playing his piece. He was so impressed that he helped them record the work, which was not only their first recording experience but also an important invitation to the world of contemporary composers – after Messiaen, they worked with György Ligeti, Pierre Boulez and Luciano Berio. Their career breakthrough came with their original arrangement of George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue, which became one of the first gold records of classical music.

The Labèque sisters have performed in famous concert halls from the Musikverein in Vienna to Carnegie Hall in New York, have been guests at major festivals (BBC Proms, Salzburg, Tanglewood) and have appeared with the most celebrated orchestras in the world (Berlin Philharmonic, Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, La Scala Orchestra, Los Angeles Philharmonic, etc.). “We don’t have the huge repertoire of a solo pianist or a violinist, but we have all the more freedom to create our own music and our own projects,” say the sisters, who collaborate with Baroque music ensembles (such as The English Baroque Soloists with Sir John Eliot Gardiner and Il Giardino Armonico with Giovanni Antonini), but they also venture into the field of “non-artificial” (natural) music (Katia even played in a rock band).

The problem of the limited repertoire for piano duo is also solved by addressing contemporary composers. In addition to the above mentioned, in 2015 they gave the world premiere of Philip Glass’s Double Concerto with the Los Angeles Philharmonic and Gustavo Dudamel. Two years later they premiered Bryce Dessner’s Concerto for Two Pianos expressly written for them, and recorded it for the album “El Chan”. The Labèques also performed this piece in Prague’s Rudolfinum – although due to the pandemic (2021) without an audience, only in a streamed version. However, this was not the Labèque sisters’ first meeting with the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra (whose chief conductor Semyon Bychkov is Marielle Labèque’s husband). In April 2017, the Dvořák Hall witnessed their performance of Poulenc’s Concerto for Two Pianos, and a year later they made their solo debut there.

Evelina Dobračeva soprano

Dramatic soprano Evelina Dobračeva began her musical career studying accordion, conducting and teaching in her hometown Syzran, Russia. She graduated with a diploma before relocating to Germany, where she began singing under the tuition of Norma Sharp, Snezana Nena Brzakovic and Julia Varady at the Hanns Eisler Music College Berlin. She claimed the highest level of scholarship from the German Republic and was a prize winner at the Würzburg Mozart Competition in 2006.

She performed at the Bayerische Staatsoper (Khovanshina), Cincinnati Opera (Tosca), Bolshoi Theatre (Pique Dame) and Theater St Gallen (Onegin and Fidelio). In concert she has recently sung Erwartung with the Capella Cracoviensis, the War Requiem with the LPO conducted by Vladimir Jurovsky, at Musikverein Vienna; Carnegie Hall and with the Spanish Radio, Verdi Requiem with the Scottish Orchestra, Mozarteum Salzburg, The Bells with Santa Cecilia Orchestra and Shostakovich 14 with Maggio Musicale Fiorentino.

Lucie Hilscherová mezzo-soprano

The Czech mezzo-soprano Lucie Hilscherová makes guest appearances at the National Theatre in Prague, the National Moravian-Silesian Theatre in Ostrava, the J. K. Tyl Theatre in Pilsen, the Silesian Theatre in Opava, the State Theatre in Košice, and the Mannheim National Theatre. She has also appeared as Háta in The Bartered Bride in Tokyo (2010, Tokyo Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra, Suntory Hall, conductor Leoš Svárovský) and London (2011, BBC Symphony Orchestra, Barbican Hall, conductor Jiří Bělohlávek).

She is in demand for concert performances of the lieder and oratorio repertoire, and she also enjoys interpreting the works of contemporary composers. She has collaborated with important orchestras and conductors, appearing at such festivals as Musikfest Stuttgart, Beethovenfest Bonn, Grafenegg Musik-Sommer, Prague Spring, the Easter Festival of Sacred Music in Brno, Smetana’s Litomyšl, the St. Wenceslas Music Festival, and the Peter Dvorský International Music Festival in Jaroměřice.

Aleš Briscein tenor

Two-time Thalia Award winner Aleš Briscein is a sought-after guest at Czech and foreign theatres and concert halls. He originally studied clarinet and saxophone, then opera singing at the Prague Conservatoire. Thereafter, he furthered his studies at the University of West Bohemia in Pilsen. He has performed at the prestigious Salzburg, Edinburgh, and Prague Spring festivals, including having sung the main tenor role of part Jonathan in the world premiere of the oratorio Judas Maccabeus by Sylvie Bodorová. For the Decca label, he make a CD recording of Pavel Haas’s opera The Charlatan, and he has sung in Alban Berg’s Wozzeck in Valencia and in Zemlinsky’s opera Der Zwerg with the Odyssey Opera in Boston. His range of repertoire is very broad, and he enjoys devoting himself to early music and sacred works. Although he has appeared in concert collaborating with many important orchestras, his career focuses on opera. He is a regular guest in Prague with the National Theatre and the State Opera, and abroad he works in close cooperation with the Opéra National de Paris. He has also appeared on the stages of the Teatro Real in Madrid, Vienna’s Volksoper, Berlin’s Komische Oper, the Bavarian State Opera, and Oper Graz.

Jan Martiník bass

Vocal beauty combined with brilliant technique and comic talent have made Jan Martiník, a graduate of the Janáček Conservatoire and of the University of Ostrava, into one of the leading singers of the younger generation. Despite having just recently celebrated his 30th birthday, he already has several competition successes to his credit (victories at the Antonín Dvořák International Competition in Karlovy Vary and at BBC Cardiff Singer of the World, laureate of the Yelena Obraztsova International Singing Competition in Moscow, finalist at Placido Domingo’s singing competition Operalia). He has made guest appearances at Prague’s National Theatre and has held engagements first at the National Moravian-Silesian Theatre in Ostrava, then at Berlin’s Komische Oper and the Staatsoper Unter den Linden.

He has appeared in concert with such famed orchestras as the Czech Philharmonic (for example in the Glagolitic Mass on a European tour and on a floating stage on the Vltava), the Rotterdam Philharmonic, the Staatskapelle Dresden, the BBC Symphony Orchestra, the King’s Consort, and Collegium 1704. He is especially acclaimed in the art song repertoire for the purity of his interpretations of Schubert’s Winterreise and of Dvořák’s Biblical Songs.

Edinburgh Festival Chorus choir

Aidan Oliver choirmaster

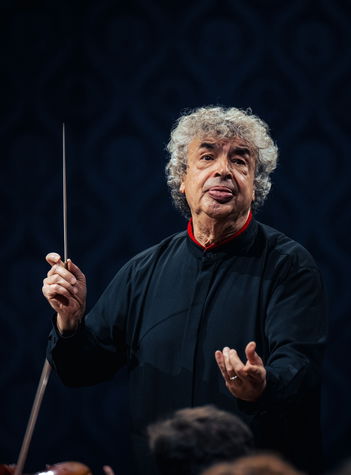

Semyon Bychkov conductor

In addition to conducting at Prague’s Rudolfinum, Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic in the 2023/2024 season, took the all Dvořák programmes to Korea and across Japan with three concerts at Tokyo’s famed Suntory Hall. In spring, an extensive European tour took the programmes to Spain, Austria, Germany, Belgium, and France and, at the end of year 2024, the Year of Czech Music culminated with three concerts at Carnegie Hall in New York.

Among the significant joint achievements of Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic is the release of a 7-CD box set devoted to Tchaikovsky’s symphonic repertoire and a series of international residencies. In 2024, Semjon Byčkov with the Czech Philharmonic concentrated on recording Czech music – a CD was released with Bedřich Smetanaʼs My Homeland and Antonín Dvořákʼs last three symphonies and ouvertures.

Bychkovʼs repertoire spans four centuries. His highly anticipated performances are a unique combination of innate musicality and rigorous Russian pedagogy. In addition to guest engagements with the world’s major orchestras and opera houses, Bychkov holds honorary titles with the BBC Symphony Orchestra – with whom he appears annually at the BBC Proms – and the Royal Academy of Music, who awarded him an Honorary Doctorate in July 2022. Bychkov was named “Conductor of the Year” by the International Opera Awards in 2015 and, by Musical America in 2022.

Bychkov began recording in 1986 and released discs with the Berlin Philharmonic, Bavarian Radio, Royal Concertgebouw, Philharmonia Orchestra and London Philharmonic for Philips. Subsequently a series of benchmark recordings with WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne featured Brahms, Mahler, Rachmaninov, Shostakovich, Strauss, Verdi, Glanert and Höller. Bychkov’s 1993 recording of Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin with the Orchestre de Paris continues to win awards, most recently the Gramophone Collection 2021; Wagner’s Lohengrin was BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Year (2010); and Schmidt’s Symphony No. 2 with the Vienna Philharmonic was BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Month (2018).

Semyon Bychkov has one foot firmly in the culture of the East and the other in the West. Born in St Petersburg in 1952, he studied at the Leningrad Conservatory with the legendary Ilya Musin. Denied his prize of conducting the Leningrad Philharmonic, Bychkov emigrated to the United States in 1975 and, has lived in Europe since the mid-1980’s. In 1989, the same year he was named Music Director of the Orchestre de Paris, Bychkov returned to the former Soviet Union as the St Petersburg Philharmonic’s Principal Guest Conductor. He was appointed Chief Conductor of the WDR Symphony Orchestra (1997) and Chief Conductor of Dresden Semperoper (1998).

Compositions

Antonín Dvořák

Carnival Overture, Op. 92

“Whatever we have in Czech history that is truly great has grown from the bottom up!” This sentence by the famous Czech author Jan Neruda tells us a great deal about the history of the Czech nation and its great figures. It certainly applies unreservedly to Antonín Dvořák, whose growing artistry took him from a little village to the world’s greatest metropolises.

When Neruda wrote these words in 1884, he was 50 years old. And what was Antonín Dvořák doing in 1891 at age 50? He was a famous, sought-after composer, an artist whose popularity had long since crossed the borders of Austria-Hungary and spread all over Europe. It was in the year of his 50th birthday that he was offered the directorship of the National Conservatory of Music in New York. He considered the matter very carefully, consulting with many of the people who were close to him. For example, he wrote to his friend Alois Göbl in June 1891: “I’m supposed to go to America for two years! […] Should I accept the offer? Or not? Send me word.” Dvořák had never been very fond of celebrations, so it is no surprise that in early September he refused to take part in celebrations in Prague for his 50th birthday because he was spending time with his family at his beloved summer home in Vysoká, where he went to rest and to compose. Four days after his birthday (12 September 1891), he finished orchestrating Carnival Overture, Op. 92, the second work in a cycle of three concert overtures that are programmatic in character. We do not have a concrete programme from the composer, but he clearly realised something here that no one would have expected from him in the realm of symphonic music. Two years earlier, he had already gone down this path in chamber music with his Poetic Tone Pictures, Op. 85, thirteen pieces for solo piano, about which he jokingly commented: “I’m not just an absolute musician, but also a poet.” Dvořák had originally conceived his triptych of concert overtures depicting three aspects of human life as a single whole with the title “Nature, Life, and Love”. All three overtures are also carefully motivically interconnected. Ultimately, however, the composer told his publisher Simrock that his overtures “each can also be played separately”, and he gave them the opus numbers and titles In Nature’s Realm, Op. 91, Carnival Overture, Op. 92, and Othello, Op. 93. The first performance of all three overtures took place on 28 April 1892 at the Rudolfinum in Prague at the composer’s farewell concert before his departure for America, with Dvořák himself conducting the orchestra of the National Theatre. Dvořák also conducted their second performance, this time across the ocean on 21 October 1892 at New York’s Carnegie Hall.

Bohuslav Martinů

Concerto for Two Pianos and Orchestra H 292

Martinů was commissioned to composed the Concerto for Two Pianos and Orchestra by the husband and wife Pierre Luboschutz and Genia Nemenoff, who together constituted a piano duo. Martinů met them in 1942 in the USA at the summer orchestral festival in Tanglewood, where he taught composition. He wrote the concerto during the first two months of 1943, and he dedicated it to the couple. In the programme for the world premiere on 5 November 1943 in Philadelphia (with the Philadelphia Orchestra conducted by Eugen Ormandy and the dedicatees as the soloists), Martinů wrote: “In the Concerto, [...] I have used the pianos for the first time in the purely ʻsoloʼ sense, with the orchestra as accompaniment. The form is free; it leans rather toward the Concerto grosso. It demands virtuosity, brilliant piano technique, and the timbre of the same two instruments calls forth new colours and new sonorities.” In this way, he distanced himself from earlier concertante compositions in which he had also used two pianos in solo episodes: the Concerto grosso, H 263 (1937) and the Tre ricercari, H 267 (1938). The Belgian piano duo of Janine Reding-Piette and Henry Piette (also a married couple) enjoyed tremendous success with this Concerto from the mid-1950s onwards. They were “electrified” by the work, and they asked Martinů to compose a second concerto for two pianos and orchestra for them. Although the composer is said to have agreed, the work ultimately was never written because of his deteriorating health. After one performance, a critic wrote enthusiastically: “This concerto will be like the Tour de France; it’s going on a Tour du monde.” It seems that the Concerto for Two Pianos and Orchestra is the “ideal type” not only for the concerto grosso form, as the composer commented, but also for piano duos consisting of close relatives, which is again the case at this evening’s performance.

Leoš Janáček

Glagolitic Mass, a cantata for soloists, choir, orchestra and organ

Among great creative figures, Leoš Janáček is remarkable in that the older he got, the more “youthful”, original, and modern the music that he wrote became. This was perhaps because he had lost everything. Released by the cruelty of fate from his ties and concerns for his parents and his children, he was truly able to find himself. He cast aside conventions and tried to get to the heart of things.

Janáček’s Glagolitic Mass is one of the most powerful sacred compositions in music history. The 72-year-old composer wrote the music to the text in Old Church Slavonic in 1926 at his favourite spa, Luhačovice. “The rain in Luhačovice is pouring, just pouring. I look out of the window at the gloomy mountain Komoň. The clouds come rolling in, and the wind tears and scatters them. […] The darkness becomes denser and denser. Now I look out into the black of night; lightning slashes into the darkness.” That is how Janáček described the atmosphere that August, when he began writing his Glagolitic Mass. The decision was made quickly. Although he had taken an interest in the Old Church Slavonic text of the Mass a few years beforehand and had made a few sketches, the music that he ultimately began writing in Luhačovice had nothing in common with those sketches. For Janáček, starting the new work was quite emotional. His ideas had to mature, but once creative fervour had taken hold, he composed quickly. He sketched out the entire Mass in just three weeks! By October 1926, he had finished it. He made more quite substantial changes after the premiere, which took place on 5 December 1927 in Brno. Janáček was able to make cuts. He is never verbose; he is precise.

For example, in the movement “Věruju” (Credo) he shortened the orchestral interlude that contained a very powerful passage inducing the atmosphere before the choir begins singing about Christ’s crucifixion. Janáček originally scored this harsh passage for three (!) sets of tympani, and he combined them with expressive music for brass and organ. In a letter to Kamila Stösslová he wrote: “…so I’m doing a bit of a depiction of the legend that when Christ was stretched out on the cross, the heavens were torn. So I wrote rumbling and lightning…” His wife Zdena supposedly told him: “Leoš, that’s impossible; you’re cursing at the Lord God there.” And a while later Janáček said: “So I’ve gotten rid of the tympani there…”

Although the Glagolitic Mass is a musical setting of a liturgical text, the work is not confessional in character. To Ludvík Kundera’s review, in which he called the composer an “old man” and a “firm believer”, Janáček’s reply was “No old man, no believer, you youngster”. This is often quoted, but we must take it with a grain of salt. Janáček was unquestionably a spiritual person. He was raised in the environment of the church at the Benedictine Monastery in Old Brno. However, he was not a practicing Catholic. We know only that he brought his children up in faith and prayer. He apparently felt distanced from the Catholic Church, so he was attracted to the idea of writing a Mass, but to the Old Church Slavonic text.