Programme

Maurice Ravel

Five Greek Folk Songs (8')

Béla Bartók

Five Hungarian Folk Songs, Sz 101 BB 108 (6')

— Intermission —

Gustav Mahler

Symphony No. 9 in D major (81')

Secure your seat for the 2025/2026 season – presales are open.

Choose SubscriptionThe Velvet Revolution Concerts are intended to remind us of our civilisation’s democratic values and to present a programme that supports those ideals. For the occasion, the season’s artists-in-residence have chosen songs by Maurice Ravel and Béla Bartók and the final symphony of Gustav Mahler—a hymn celebrating life and humanity.

Duration of the programme 1 hour 55 minutes

Maurice Ravel

Five Greek Folk Songs (8')

Béla Bartók

Five Hungarian Folk Songs, Sz 101 BB 108 (6')

— Intermission —

Gustav Mahler

Symphony No. 9 in D major (81')

Magdalena Kožená mezzo-soprano

Simon Rattle conductor

Czech Philharmonic

Sir Simon Rattle recalled: “It isn’t often that I fall in love with an orchestra, and most of my relationships with orchestras date back quite a while. But when I conducted the Czech Philharmonic for the first time, the kind of music I would like to hear the orchestra play occurred to me immediately. It has been able to preserve its own typical sound, which is perfectly suited to Mahler. One of my old mentors was Berthold Goldschmidt, who conducted the British premiere of Mahler’s Third Symphony, among other things. Of the many wonderful things he told me about Mahler’s Ninth, one thing really stuck with me: ‘Remember that Mahler put everything he hated about Austria into the first scherzo and everything he hated about Vienna into the second one. If you have that in mind, you’ll never be far off the mark.’”

Magdalena Kožená soprano

Like on many past occasions, Magdalena Kožená is returning to her homeland with her husband, Sir Simon Rattle. Kožená, a graduate of the Brno Conservatoire and of the Academy of Performing Arts in Bratislava, came to worldwide attention thanks in part to victory at the International Mozart Competition in 1995; four years later she signed an exclusive contract with the label Deutsche Grammophon, for which she has released many award-winning recordings (Gramophone Award, Echo Klassik, Diapason d’Or etc.). She divides her performing activities between recitals, concert appearances, and operatic roles including regular guest appearances at New York’s Metropolitan Opera. She also performs in such non-classical genres as swing and flamenco. Her classical repertoire is of remarkable breadth, ranging from the baroque era and collaborations with ensembles specialising in early music to the classical and romantic repertoire, in which she has won fame in part as a proponent of Czech music, and onwards to the music of today.

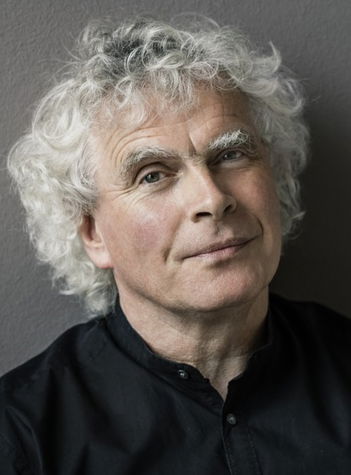

Simon Rattle conductor

We have seen one of today’s most distinguished conductors, Sir Simon Rattle, relatively often at the Rudolfinum in recent years. His long-term cooperation with the Czech Philharmonic has led to his appointment together with his wife, mezzo-soprano Magdalena Kožená, as Artist-in-Residence for the 2022/2023 season. At his appearances with the Czech Philharmonic, he has performed a number of symphonic works and, most notably, compositions for voices and orchestra from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the repertoire for which Rattle has been the most acclaimed. He appeared most recently at the Rudolfinum in February 2024 with the pianist Yuja Wang, with whom he made a Grammy-nominated recording from their joint tour of Asia in 2017. From the 2024/2025 season, he becomes the Principal Guest Conductor of the Czech Philharmonic.

A native of Liverpool and a graduate of the Royal Academy of Music has held a series of important positions in the course of his long career. He came to worldwide attention as the chief conductor of the Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, where he was employed for a full 18 years (for eight years as its music director); next came 16 years with the Berlin Philharmonic (2002–2018; artistic director and chief conductor) and six years with the London Symphony Orchestra. He opened the 2023/2024 season as chief conductor of the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra. He also leads the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment with the title of “principle artist”, and he is the founder of the Birmingham Contemporary Music Group. Besides holding full-time conducting posts, he maintains ties with the world’s leading orchestras and gives concerts frequently in Europe, the USA, and Asia.

He has made more than 70 recordings for EMI (now Warner Classics). He has won a number of prestigious international awards for his recordings including three Grammy Awards for Mahler’s Symphony No. 10, Brahms’s German Requiem, and Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms, which he recorded with the Berlin Philharmonic.

Besides the prizes mentioned above, Rattle’s long-term partnership with the Berlin Philharmonic also led to the new educational programme Zukunft@Bphil, which has achieved great success. Even after moving on from that orchestra, Rattle did not abandon his engagement with music education, and he has taken part together with the London Symphony Orchestra in the creation of the LSO East London Academy. Since 2019, that organisation has been seeking out talented young musicians, developing their potential free of charge regardless of their origins and financial situation.

Maurice Ravel

Five Greek Folk Songs

Ravel was a leading representative of musical Impressionism and composed such famous works as Bolero, La valse, and the ballet Daphnis et Chloé. In the 1920s and ’30s, Maurice Ravel was known all around the world, but his early music remained unfamiliar. At the very end of the 19th century, he studied at the Paris Conservatoire, dropping out on two occasions. Then he applied unsuccessfully five times for the prestigious Prix de Rome, a composition competition that offered a cash prize and a study visit in Italy. Ravel was a rebel and even declared himself to be an anarchist. At age 25, he became a member of a group of radical left-wing artists known as Les Apaches (sometimes called the “Hooligans”) along with the composer Manuel de Falla and the Greco-French music critic Michel-Dimitri Calvocoressi, who encouraged Ravel’s interest in exotic musical influences. He also showed Ravel folk songs from the island Chios, the texts of which he had translated into French, and he asked the composer to arrange them. Between 1904 and 1906, Ravel composed eight songs for voice and piano, which were premiered at a lecture given by Calvocoressi. Ravel chose five of the songs for publication as a cycle with piano accompaniment as well as an orchestral version. The orchestration was done much later in the 1930s, by which time the composer was in poor health. For this reason, Ravel orchestrated only two of the songs (1 and 5). The orchestrations of the other three are by Ravel’s pupil, the French conductor and composer Manuel Rosenthal (1904–2003). The songs with orchestral accompaniment appeared in print in 1935, two years before Ravel’s death.

The pithy folk texts are at times high spirited and at other times lyrical. Ravel set them to music as miniatures coming one immediately after another. In the first song, a man asks his bride-to-be to get up and enjoy the morning with him, and at the end he proposes that they be married. The music is at a moderate tempo and is in G minor, although Ravel often omits the third of the chord, so we hear only an open fifth. Next is a calm, pious song in G sharp minor, then the dynamic third song in G major is a celebration of manliness and a declaration of love. The Song of the Lentisk Gatherers (Lentisk is a bush that produces mastic, a resin with healing properties) is again slow and panegyrical. The cycle ends with a quick, joyous dance melody, concluding with a carefree “tra la la”. The cycle’s structure is characterised by a sequence of keys within a narrow range: G minor – G sharp minor – G major – A major – A flat major.

Béla Bartók

Five Hungarian Folk Songs, Sz 101, BB 108

The Hungarian composer Béla Bartók devoted much of his career to collecting and arranging folk songs both for the sake of their preservation and as a source of inspiration for his own music. In 1905, he and his colleague Zoltán Kodály set out into the Hungarian countryside to collect folk songs. Bartók gradually expanded his activity to include Slovak and Romanian songs as well as folk music from Arabia, Turkey, the Ukraine, Wallachia, and elsewhere. He became one of the world’s acknowledged authorities in the field and lectured on the importance of folk music and its influence on modern composition. His studies were published in many countries. In 1929 he issued his first collection of songs with original adaptations of folk melodies. Maria Basilides sang the premiere of the Twenty Hungarian Folk Songs with Bartók at the piano in Budapest in January 1930. A few years later, Bartók chose five songs in contrasting moods from the collection and orchestrated the accompaniment on commission for the Budapest Philharmonic, which was celebrating the 80th anniversary of its founding in 1933. The result was a new cycle, Five Hungarian Folk Songs with a colourful, inventive orchestral accompaniment, creating a warmer, more festive counterpart to the starker piano version. Maria Basilides also premiered the orchestral version.

The cycle begins with the longest and darkest of the songs, A tömlöcben (In Prison), about the suffering endured by a prisoner, his prayers for his wife and child, and his hope of being released. The accompaniment of the outer sections is rather simple, deliberately monotonous, and gloomy, drawn from the actual folk material. The contrasting middle section is agitated, then the conclusion returns to a state of gloomy melancholy. Next, Régi kerseves (Old Lament) tells of solitude and the sorrow of life, from which the only liberation is death. Again, the sorrow is underscored by the simple empathy of the orchestral accompaniment, but we no longer feel the despair of the first song.

The two Nuptial Serenades are in a much happier mood. The first is a wedding song with striking orchestration that depicts a courting couple riding through the countryside on horseback. Sounds reminiscent of bells on a horse’s harness and other effects supplement the cheerful vocal line, creating a charming mood. The second serenade tells a humorous story about a frog being roasted at the Virag family home and about the people who got portions of this dubious meal. The accompaniment of this peculiar song is energetic and colourful, and the vocal line contains grotesque figurations employing strong rhythms, pauses, tempo changes, and onomatopoeia. Between the serenades, Bartók inserted the contrasting song Panasz (Complaint) at a slow, swinging tempo, almost reminiscent of the blues. The vocal part expresses worry over a sick woman and the singer’s desire bear her suffering for her.

Gustav Mahler

Symfonie č. 9 D dur

Beginning in 1908, Gustav Mahler was living in New York—he was the chief conductor of the Metropolitan Opera and later of the newly established New York Philharmonic as well. Nonetheless, Austria was still the place where he felt truly at home. Mahler rented an isolated house not far from the Tyrolean village Toblach, where he conceived his Ninth Symphony during the three summer months of 1909. He wrote out a continuous draft there, then he finished the orchestration back in New York. Mahler, like Beethoven, Bruckner, and Dvořák, was not able to escape the “curse” of going past nine symphonies, although he attempted to do by not numbering Das Lied von der Erde as a symphony, just in case.

Mahler was gravely ill by then, and he did not live to hear his Ninth. Bruno Walter led the Vienna Philharmonic in the symphony’s premiere in the Great Hall of Vienna’s Musikverein on 26 June 1912, the year after the composer’s death. The adherents of the Viennese avant-garde immediately grasped the work. Alban Berg called it the most beautiful thing that Mahler had ever written, and Arnold Schoenberg regarded the symphony as transcendent: “It almost seems as though this work must have a concealed author who used Mahler merely as his spokesman, as his mouthpiece. This symphony is no longer couched in the personal tone. It consists, so to speak, of objective, almost passionless statements of a beauty which becomes perceptible only to one who can dispense with animal warmth and feels at home in spiritual coolness. [...] It seems that the Ninth is a limit. He who wants to go beyond it must pass away. It seems as if something might be imparted to us in the Tenth which we ought not yet to know, for which we are not yet ready. Those who have written a Ninth stood too near to the hereafter. Perhaps the riddles of this world would be solved, if one of those who knew them were to write a Tenth. And that probably is not to take place”, said Schoenberg in a Prague lecture about Mahler in 1912. The Prague premiere of the symphony took place on 6 November 1918 with the Czech Philharmonic conducted by Otakar Ostrčil, a devoted interpreter of Mahler’s legacy. Another devotee was Alexander Zemlinsky, who led the work on 14 January 1923 with the orchestra of the New German Theatre and several more times in the 1930s with the Czech Philharmonic as a guest conductor.

Unlike the preceding Eighth Symphony or Das Lied von der Erde, the Ninth Symphony employs purely instrumental forces—a large orchestra with many wind and percussion instruments. The four movements have little to do with the classical symphonic form, including their peculiar sequence of keys (D major, C major, A minor, D flat major). The long, slow outer movements form an ideological and philosophical centre of gravity, and the pair of movements in their midst provide the maximum conceivable contrast with their deliberate vulgarity and grotesqueness. The scherzo movement is to be played “at the tempo of a leisurely ländler” and “rather clumsily and very coarsely”, and it has been likened to a dance of death. The third movement is subtitled “Rondo. Burleske” and is to be played “very defiantly”. Mahler dedicated it “to my brothers in Apollo”. Here, the revelry stands above an abyss, and we are treated to a feast of Mahler’s legendary orchestral artistry. However, the meditative culmination of the colossal 80-minute work is characteristically entrusted just to the intimate sound of the strings playing at the softest dynamics, fading away to nothingness and breaking all bonds with earthly life.

The Velvet Revolution Concerts are intended to remind us of our civilisation’s democratic values and to present a programme that supports those ideals. For the occasion, the season’s artists-in-residence have chosen songs by Maurice Ravel and Béla Bartók and the final symphony of Gustav Mahler—a hymn celebrating life and humanity.