9. 3. 16:00 London

On paper, it sounds fantastic: a two-week business trip to Vienna, Amsterdam, London, Paris, and Bruges, performing in the most beautiful concert halls in Europe. Who would complain? But then you actually have to, well, endure the whole journey…

“Sometimes it’s tough because you have to catch a flight in the morning, transfer to another city, take a bus to the hotel, and perform in the evening. And the next day, it starts all over again,” says Jan Fišer, describing the life of a touring musician. As concertmaster, he has additional responsibilities on top of that.

“I help interpret between the conductor and the orchestra and vice versa. Then there’s the public aspect—representing the orchestra at various events—but otherwise, it’s not that different from what audiences know from home,” he explains.

And another concern: Jan Fišer plays a very valuable, moreover borrowed instrument. He prefers not to send it with the rest of the equipment in a truck. “My violin is part of my identity, my companion. I want to have it with me at all times. In the hotel, it has a place of honor,” he admits, revealing that on tour, he falls asleep and wakes up with his instrument always in sight.

Amid the constant travel and tight schedules, getting enough rest is crucial. That’s why he’ll decline an invitation for a drink in favor of a pre-concert walk. He could easily work as a London tour guide—he navigates the half-hour walk from his hotel to the Barbican without needing a map. “I’ve been here a few times…” he chuckles.

Recently, he visited with his family, so he has already explored the landmarks, museums, and galleries. “I’d rather go to the park. Everything will start blooming soon—it’s going to be beautiful,” he says, looking forward to his day off. And that brings us back to the question of how to unwind on long tours. “You try to make the most of every minute. Because when you step onto the stage and start playing, you need to be fully focused, forget everything else, and think only about the audience and the music.”

Like most musicians, Jan Fišer looks forward to performing in stunning concert halls. His favorite is the Musikverein—not just for its aesthetic beauty but also for its historical significance. What other place in the world better embodies the tradition of musical Romanticism? Among modern halls, he’s particularly fond of Tokyo’s Suntory Hall.

For musicians, concert halls are primarily workplaces—they need to understand them acoustically. “We know most halls well, so adaptation is quick. The most important thing is tuning into each other so that we feel connected, listening and responding to one another. That’s what makes the music sound cohesive to the audience,” Fišer explains.

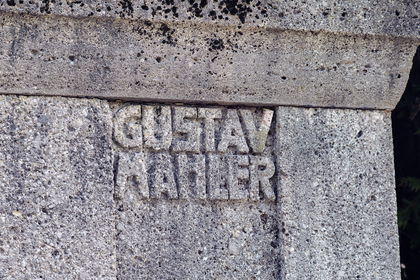

He shares a memory from the Elbphilharmonie, where he performed with a trio. He was staying at a local hotel. “I was lying in the bathtub, looking out the window at the ships,” he recalls. And he adds that Prague, too, deserves its own Vltava Philharmonic Hall. “The orchestra needs a new hall—even Mahler’s music is too much for Dvořák Hall. Still, I always love returning to the Rudolfinum. There’s no place like home.”